The E(38) boson - Understanding the Dubna measurements

By Chris Austin. 30 November 2020.

An earlier version of this post was published on another website on 3 September 2012.

As I reported in an earlier post, two weeks ago seven physicists announced the

observation of a new light boson of mass 38 MeV at the Nuclotron particle

accelerator in Dubna, near Moscow. The new boson, named the E(38), is not

predicted by the Standard Model of the strong and electroweak interactions,

and if the observation is confirmed, it will be the first discovery of an

elementary particle not predicted by the Standard Model, since the Standard

Model became established in the 1970's.

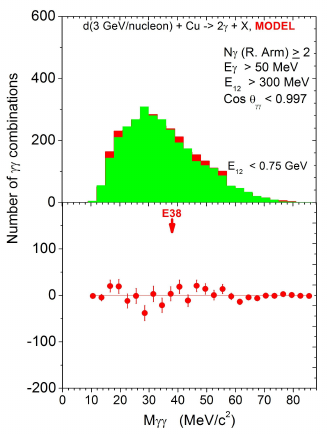

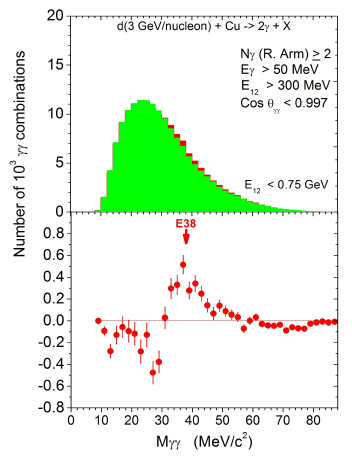

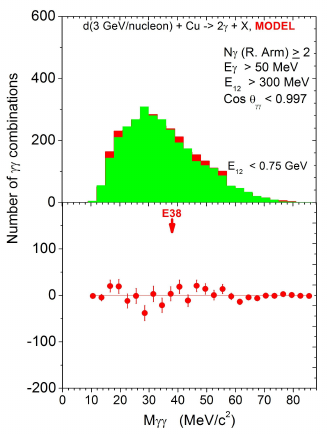

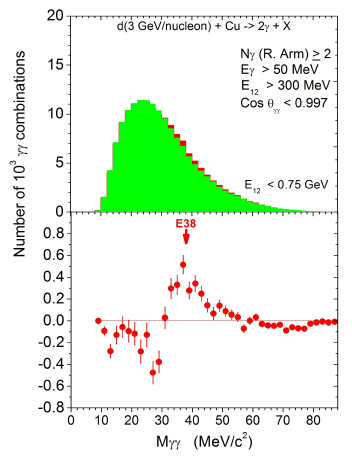

The evidence for the E(38) boson was a small excess above background, peaked

at about 38 MeV, in the distributions of the invariant mass of photon pairs

produced in three different processes, involving the scattering of beams of

deuterons or protons aimed at carbon or copper targets. For example in

Figure 2(a) of the article arXiv:1208.3829 announcing the observation of the

E(38) boson, which I am reproducing here

with permission, the green histogram

in the top panel is the Standard Model background, and the small red excess

above the background, which is largest at about 38 MeV, is attributed to pairs

of photons from the decay of the E(38) boson.

The lower panel shows the

excess after subtraction of the Standard Model background. The statistical

significance of the excess above background centred at about 38 MeV is about 5

sigma, which is the usual standard for discovery of a new particle in high

energy physics.

The lower panel shows the

excess after subtraction of the Standard Model background. The statistical

significance of the excess above background centred at about 38 MeV is about 5

sigma, which is the usual standard for discovery of a new particle in high

energy physics.

As Tommaso Dorigo has pointed out, the announcement article arXiv:1208.3829 does not

give any details of how the background distribution of the photon pair

invariant mass was determined. Since the background is about 14 times larger

than the claimed signal at the peak of the signal for the measurements shown

in Figure 2(a), and is at least 6 times larger than the claimed signal at the

peak of the signal for all the measurements shown in arXiv:1208.3829, Tommaso

is understandably sceptical about whether the signal is really there.

However the authors refer to another paper for a description of the

experimental equipment, and the details in this reference appear to address

most of the points raised by Tommaso.

To explain in more detail how the Dubna group observed a signal for the

candidate E(38) boson, and how they measured the background, it is convenient

to use units of measurement such that the speed of light  is equal to 1, so

that if, for example, distance is measured in metres, then time is measured

not in seconds but in units of

is equal to 1, so

that if, for example, distance is measured in metres, then time is measured

not in seconds but in units of

nanosec.

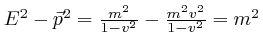

Then the units of energy, momentum and mass all become the same, so that

Einstein's relation

nanosec.

Then the units of energy, momentum and mass all become the same, so that

Einstein's relation  between the total energy

between the total energy  of a particle that

is not moving, and its mass

of a particle that

is not moving, and its mass  , becomes

, becomes  .

.

The total energy  of a particle of mass

of a particle of mass  moving at speed

moving at speed  can now be

written as

can now be

written as

, which for

, which for  small compared to 1,

so that the particle is moving slowly compared to the speed of light, is

approximately equal to

small compared to 1,

so that the particle is moving slowly compared to the speed of light, is

approximately equal to

, which is the sum of its rest

energy

, which is the sum of its rest

energy  and its kinetic energy

and its kinetic energy

according to Newton's

mechanics. The kinetic energy of a particle that is not necessarily moving

slowly compared to the speed of light is defined to be

according to Newton's

mechanics. The kinetic energy of a particle that is not necessarily moving

slowly compared to the speed of light is defined to be

. The sum of the total energies

. The sum of the total energies  of all the

particles involved in a collision process is always the same before and after

the collision, even if new particles are produced or particles disappear

during the collision.

of all the

particles involved in a collision process is always the same before and after

the collision, even if new particles are produced or particles disappear

during the collision.

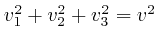

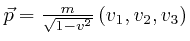

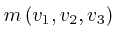

If the velocity vector of a particle is

, where

, where

, then its momentum vector is

, then its momentum vector is

, which for

, which for  small

compared to 1, is approximately

small

compared to 1, is approximately

, which is its

momentum vector according to Newton's mechanics. The sum of the momentum

vectors of all the particles involved in a collision is always the same before

and after the collision. The difference

, which is its

momentum vector according to Newton's mechanics. The sum of the momentum

vectors of all the particles involved in a collision is always the same before

and after the collision. The difference

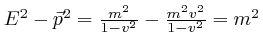

between the square of a particle's total

energy

between the square of a particle's total

energy  , and the square

, and the square

of its momentum

vector

of its momentum

vector  , is always equal to the square of its mass

, is always equal to the square of its mass  , for all possible

values of its speed

, for all possible

values of its speed  . The speed

. The speed  of a massive particle is always less

than 1, because its energy

of a massive particle is always less

than 1, because its energy  approaches infinity as its speed tends to 1.

approaches infinity as its speed tends to 1.

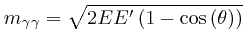

A photon is massless, and its total energy  is always equal to the

magnitude

is always equal to the

magnitude

of its momentum vector

of its momentum vector  , so that

, so that

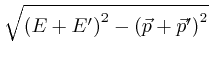

. If a particle of mass

. If a particle of mass  decays into two photons, whose

total energies are

decays into two photons, whose

total energies are  and

and  , and whose momentum vectors are

, and whose momentum vectors are  and

and

, then since

, then since  is equal to the energy of the initial

particle, and

is equal to the energy of the initial

particle, and

is equal to the momentum vector of the

initial particle, we have:

is equal to the momentum vector of the

initial particle, we have:

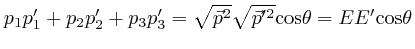

where at the first step in the second line I used

and

and

, and at the second step in the second line, I used

, and at the second step in the second line, I used

, where

, where  , which is the

Greek letter theta, is the angle between the directions of motion of the two

photons, and I explained the meaning of

, which is the

Greek letter theta, is the angle between the directions of motion of the two

photons, and I explained the meaning of

in another

post, here.

in another

post, here.

The expression

is called the invariant mass of the two photons, and from the

above formula, the invariant mass of two photons can be measured by measuring

their energies

is called the invariant mass of the two photons, and from the

above formula, the invariant mass of two photons can be measured by measuring

their energies  and

and  , and the angle

, and the angle  between their directions

of motion. Photons whose energy is about an MeV or more are often called

gamma rays or

between their directions

of motion. Photons whose energy is about an MeV or more are often called

gamma rays or  rays, where the symbol

rays, where the symbol  is the Greek letter

gamma, because that is what they were called when they were first observed

about a century ago. So I shall represent the invariant mass of the two

photons by

is the Greek letter

gamma, because that is what they were called when they were first observed

about a century ago. So I shall represent the invariant mass of the two

photons by

.

.

In the Dubna experiment, the candidate E(38) bosons are produced by a beam of

deuterons or protons incident on a copper or carbon target in the JINR

Nuclotron. The candidate E(38) bosons are detected if they are emitted

towards one of the two arms of an electromagnetic lead glass calorimeter

called the PHOTON-2. The left and right arms of the calorimeter are located

3 metres from the target, at angles  to the left of the beam and

to the left of the beam and

to the right of the beam respectively.

to the right of the beam respectively.

The kinetic energies of the deuterons were 6 GeV = 6000 MeV for the copper

target and 4 GeV = 4000 MeV for the carbon target, and the kinetic energies of

the protons were 4.64 GeV = 4640 MeV for the carbon target. These kinetic

energies are much larger than the 38 MeV mass of the candidate E(38) boson, so

if any E(38) bosons were produced, they would be unlikely to be produced

approximately at rest. Instead they would most likely fly out of the

collision with a kinetic energy somewhat smaller than the kinetic energy of

the incident deuteron or proton, but nevertheless much larger than the 38 MeV

mass of the E(38) boson. The sum of the energies of the two photons the

E(38) boson decayed into would be equal to the total energy of the E(38)

boson, so the energies of both these photons would usually also be much larger

than the mass of the E(38) boson.

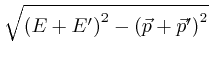

From the above formula, the invariant mass

of a photon of

energy

of a photon of

energy  in the left arm of the calorimeter and a photon of energy

in the left arm of the calorimeter and a photon of energy  in

the right arm of the calorimeter would be approximately

in

the right arm of the calorimeter would be approximately

, since

, since

, so

if

, so

if  and

and  were both much larger than 38 MeV, this would be much larger

than 38 MeV. The invariant mass

were both much larger than 38 MeV, this would be much larger

than 38 MeV. The invariant mass

of two photons can only

be much smaller than the energies of the photons if the two photons are

travelling in approximately the same direction, so to search for an excess

above the expected background distribution of the invariant mass

of two photons can only

be much smaller than the energies of the photons if the two photons are

travelling in approximately the same direction, so to search for an excess

above the expected background distribution of the invariant mass

of pairs of photons for

of pairs of photons for

in the region of 38 MeV,

the Dubna physicists measured the distribution of

in the region of 38 MeV,

the Dubna physicists measured the distribution of

for

pairs of photons in a single arm of the calorimeter, and in the article

arXiv:1208.3829, they report the distributions observed in the right arm of

the calorimeter.

for

pairs of photons in a single arm of the calorimeter, and in the article

arXiv:1208.3829, they report the distributions observed in the right arm of

the calorimeter.

To determine whether or not the measured distribution of

contains a signal from a candidate new particle decaying to pairs of photons,

it is necessary to determine and subtract the background distribution of

contains a signal from a candidate new particle decaying to pairs of photons,

it is necessary to determine and subtract the background distribution of

that results from the particles and interactions of the

Standard Model. As Tommaso pointed out, the most important backgrounds are

bremsstrahlung and the decay of neutral pions. These produce background

distributions of

that results from the particles and interactions of the

Standard Model. As Tommaso pointed out, the most important backgrounds are

bremsstrahlung and the decay of neutral pions. These produce background

distributions of

of completely different character.

of completely different character.

Bremsstrahlung, which means "braking radiation," is a smooth random

distribution of photons emitted with a wide range of energies smaller than the

energies of the electrically charged particles involved in a process, that

occurs whenever the speed or direction of motion of a charged particle

changes. A classic result of quantum electrodynamics, discovered by Felix

Bloch and Arnold Nordsieck in 1937, is that for bremsstrahlung photons whose

energies are much smaller than the energies of the electrically charged

particles involved in a process, the energies and directions of motion of the

bremsstrahlung photons emitted randomly in any process are uncorrelated with

each other. This means that the distribution of the energies and directions

of motion of pairs of bremsstrahlung photons, and in particular, their

invariant mass, can be approximately predicted, for fixed experimental

conditions, from observations of the energies and directions of motion of

single bremsstrahlung photons.

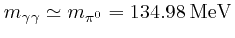

The distribution of

from the decay of neutral pions,

from the decay of neutral pions,

, is completely different. The

, is completely different. The  meson, whose mass is 134.98 MeV, is the lightest strongly-interacting

particle that can be separated by distances of more than about

meson, whose mass is 134.98 MeV, is the lightest strongly-interacting

particle that can be separated by distances of more than about

from other strongly interacting

particles. Its lifetime is

from other strongly interacting

particles. Its lifetime is

, where 1 nm = 1 nanometre is

, where 1 nm = 1 nanometre is

, and it decays to two

photons 98.8% of the time. Thus the intrinsic quantum-mechanical width of

the

, and it decays to two

photons 98.8% of the time. Thus the intrinsic quantum-mechanical width of

the  meson, which is

meson, which is  divided by its lifetime, where

divided by its lifetime, where

is Planck's constant divided by

is Planck's constant divided by

, is

, is

. So if the energy resolution and angular resolution of

the calorimeter were perfect, so that the invariant mass

. So if the energy resolution and angular resolution of

the calorimeter were perfect, so that the invariant mass

of each photon pair was measured without any error, then

the distribution of

of each photon pair was measured without any error, then

the distribution of

from the

decay of

from the

decay of  mesons, on a plot of

mesons, on a plot of

from 0 to 200 MeV,

would look like a sharp spike at

from 0 to 200 MeV,

would look like a sharp spike at

, and 0 elsewhere.

, and 0 elsewhere.

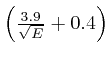

In reality neither the energy resolution nor the angular resolution of

the calorimeter is perfect, so the spike at 134.98 MeV, from  decay,

is spread out into a rounded peak.

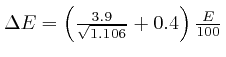

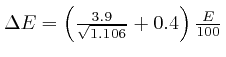

From page 5 of arXiv:0806.2790, the article which describes the calorimeter

and the way the background was measured, the energy resolution of the

calorimeter is actually

decay,

is spread out into a rounded peak.

From page 5 of arXiv:0806.2790, the article which describes the calorimeter

and the way the background was measured, the energy resolution of the

calorimeter is actually

%, where

%, where

is in units of GeV=1000 MeV, and the angular resolution of the calorimeter

is

is in units of GeV=1000 MeV, and the angular resolution of the calorimeter

is  .

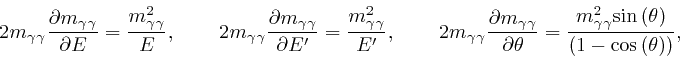

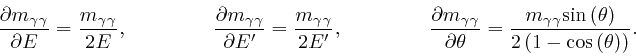

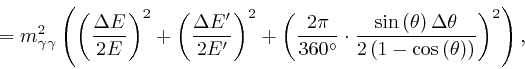

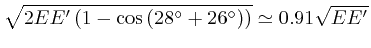

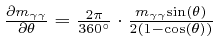

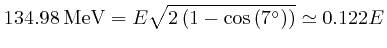

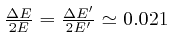

From the formula

.

From the formula

which we obtained above, and Leibniz's rule for the rate of change of

a product, which I explained in another post, here, and the formula for the

rate of change of

which we obtained above, and Leibniz's rule for the rate of change of

a product, which I explained in another post, here, and the formula for the

rate of change of

with

with  , when

, when

is measured in radians, which I explained in that post, here, we find

that for

is measured in radians, which I explained in that post, here, we find

that for  in radians:

in radians:

where I explained the meaning of an expression such as

in that post, here. So:

in that post, here. So:

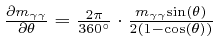

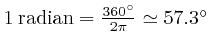

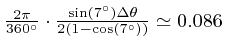

For  in degrees rather than radians, the last of these formulae

becomes

in degrees rather than radians, the last of these formulae

becomes

, since

, since

, and the other two formulae are unchanged. These

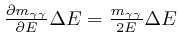

formulae mean, for example, that if the measurement of

, and the other two formulae are unchanged. These

formulae mean, for example, that if the measurement of  is in error by an

amount

is in error by an

amount  , where the symbol

, where the symbol  , which is the Greek letter Delta,

is often used to denote a change to the value of the quantity that follows it,

then the corresponding error in the measurement of

, which is the Greek letter Delta,

is often used to denote a change to the value of the quantity that follows it,

then the corresponding error in the measurement of

will be

approximately

will be

approximately

.

.

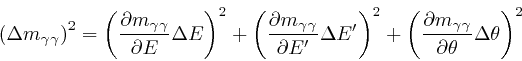

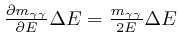

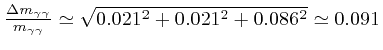

The errors in the measurements of

,

,  , and

, and  are independent of one another, so the total error in

the measurement of

are independent of one another, so the total error in

the measurement of

is on average related to the errors in

the measurements of

is on average related to the errors in

the measurements of  ,

,  , and

, and  by Pythagoras's rule:

by Pythagoras's rule:

for  in degrees.

in degrees.

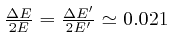

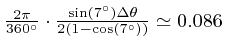

The observed photon pairs with a given value of

can have a range of different values of

can have a range of different values of  ,

,  , and

, and

, and for a representative example with

, and for a representative example with

, I'll take

, I'll take  , and

, and

, which from pages 3 to 5 of arXiv:0806.2790 is

approximately the angle between the paths of a photon that passes through the

center of the right arm of the calorimeter, and a photon that passes through

the edge of the front surface of the right arm of the calorimeter. Then from

, which from pages 3 to 5 of arXiv:0806.2790 is

approximately the angle between the paths of a photon that passes through the

center of the right arm of the calorimeter, and a photon that passes through

the edge of the front surface of the right arm of the calorimeter. Then from

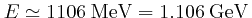

, we have

, we have

. For this value of

. For this value of  , the

formula above for the energy resolution of the calorimeter gives

, the

formula above for the energy resolution of the calorimeter gives

, so

, so

. And for

. And for

, from the angular resolution of the calorimeter, as above, we

have

, from the angular resolution of the calorimeter, as above, we

have

.

.

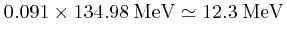

Thus for this example we have

, so

the measured distribution of

, so

the measured distribution of

is expected to show the spike at 134.98 MeV, from

is expected to show the spike at 134.98 MeV, from  decay, spread out into a peak of half-width about

decay, spread out into a peak of half-width about

, and this is in approximate

agreement with the

, and this is in approximate

agreement with the  peak seen with a deuterium beam incident on a

carbon target in Figure 8 of the article arXiv:1208.3829 announcing the

observation of the E(38) boson, although a high bin in the corresponding

measurement for a deuterium beam incident on a copper target, in Figure 9 on

page 13 of the article, spreads the

peak seen with a deuterium beam incident on a

carbon target in Figure 8 of the article arXiv:1208.3829 announcing the

observation of the E(38) boson, although a high bin in the corresponding

measurement for a deuterium beam incident on a copper target, in Figure 9 on

page 13 of the article, spreads the  peak a little further in that

case. These observations of the

peak a little further in that

case. These observations of the  peak serve to calibrate the mass

measurement.

peak serve to calibrate the mass

measurement.

From pages 8 and 15 of arXiv:1208.3829, the Dubna group used a method called

"event mixing" to measure the shape of the background distribution of

. From the description on page 5 of arXiv:0806.2790, this

means that each pair of background photons consists of two observed photons

randomly selected from different events. From the result of Bloch and

Nordsieck that I mentioned above, this would give the exact shape of the

background distribution of

. From the description on page 5 of arXiv:0806.2790, this

means that each pair of background photons consists of two observed photons

randomly selected from different events. From the result of Bloch and

Nordsieck that I mentioned above, this would give the exact shape of the

background distribution of

if the background was purely

bremsstrahlung, provided the photon energies were low enough, and the mean

number of bremsstrahlung photons of sufficient energy to trigger the

calorimeter was the same for all relevent motions of the electrically charged

particles involved, because the Bloch-Nordsieck result, that the energies and

directions of motion of the bremsstrahlung photons are uncorrelated with each

other, becomes exact in the limit where the photon energies tend to 0, because

the emission of a photon then has negligible effect on the energy and momentum

of the charged particle that emitted it.

if the background was purely

bremsstrahlung, provided the photon energies were low enough, and the mean

number of bremsstrahlung photons of sufficient energy to trigger the

calorimeter was the same for all relevent motions of the electrically charged

particles involved, because the Bloch-Nordsieck result, that the energies and

directions of motion of the bremsstrahlung photons are uncorrelated with each

other, becomes exact in the limit where the photon energies tend to 0, because

the emission of a photon then has negligible effect on the energy and momentum

of the charged particle that emitted it.

In reality, the relevant photon energies are around 10% of the kinetic

energies of the deuterons or protons in the beam incident on the target, so

the Bloch-Nordsieck result applies approximately but not exactly. This means

that the event mixing method of measuring the background introduces systematic

errors due to the violation of the energy and momentum conservation laws, when

the two-photon background is measured by randomly selecting pairs of single

photons from different events. We would also expect systematic errors to be

introduced due to contamination of the single photon bremsstrahlung background

by photons from  decay, unless the background is measured by randomly

combining pairs of single photons from events that contain exactly

one photon. This is not possible in practice, however, since the

calorimeters only cover a small fraction of the solid angle around the

interaction point. The paper arXiv:1208.3829 announcing the observation of

the E(38) boson does not discuss this source of systematic error.

decay, unless the background is measured by randomly

combining pairs of single photons from events that contain exactly

one photon. This is not possible in practice, however, since the

calorimeters only cover a small fraction of the solid angle around the

interaction point. The paper arXiv:1208.3829 announcing the observation of

the E(38) boson does not discuss this source of systematic error.

Figure 11 of the article arXiv:1208.3829 announcing the observation of the

E(38) boson, which I am reproducing here

with permission, shows the comparison

of the event mixing background with the distribution of

with permission, shows the comparison

of the event mixing background with the distribution of

for about

for about  simulated events for the deuteron beam incident on the copper

target. This provides evidence that the event mixing method adequately

represents the two-photon background over the relevant range of

simulated events for the deuteron beam incident on the copper

target. This provides evidence that the event mixing method adequately

represents the two-photon background over the relevant range of

from about 10 MeV to about 90 MeV, so that contamination of the

background by photons from

from about 10 MeV to about 90 MeV, so that contamination of the

background by photons from  decay is not significant for this range of

decay is not significant for this range of

. Comparison with Figure 2(a) of the article, which I

reproduced above, shows that the excess centred at about 38 MeV in the

measured data is absent from the simulation based on the Standard Model shown

in Figure 11.

. Comparison with Figure 2(a) of the article, which I

reproduced above, shows that the excess centred at about 38 MeV in the

measured data is absent from the simulation based on the Standard Model shown

in Figure 11.

To try to reduce systematic errors, while at the same time improving the

signal to background ratio for any genuine signal there might be, by reducing

the background without significantly reducing any genuine signal, limits

called "cuts" are imposed on the energies of the photons and on the angle

between pairs of photons, in order for a pair of photons to be counted in the

reported data. So the data that the experiment actually reports is the

distribution, or the set of number counts, of photon pairs observed in the

right-hand calorimeter, that satisfy the specified cuts. The range of

relevant values of

, which is from about 10 MeV to about 80

MeV for the search runs, is divided into intervals of 2 MeV, and the

experiment reports the number of photon pairs that satisfy the specified cuts,

for

, which is from about 10 MeV to about 80

MeV for the search runs, is divided into intervals of 2 MeV, and the

experiment reports the number of photon pairs that satisfy the specified cuts,

for

in each of about 35 intervals of 2 MeV. (For the

calibration runs, where the

in each of about 35 intervals of 2 MeV. (For the

calibration runs, where the  peak rather than a possible new boson at

38 MeV was the target of the observations, the observations covered the range

of

peak rather than a possible new boson at

38 MeV was the target of the observations, the observations covered the range

of

from about 60 MeV to about 250 MeV, and this range was

divided into intervals of 10 MeV.)

from about 60 MeV to about 250 MeV, and this range was

divided into intervals of 10 MeV.)

The cuts have to be applied in exactly the same way to the observed data and

to the measured or modelled background. So for the event mixing method of

measuring the background that the Dubna group used, each pair of background

photons, which comprises two photons randomly selected from different events,

is accepted or rejected according to the specified cuts on the energies of the

photons and the angle between their directions of motion, exactly as if the

two photons were from the same event.

As Tommaso

pointed out, the necessity of applying selection cuts to the data

means there is a danger that physicists eager to discover a new particle

might "tune the cuts", so as to create the appearance of a signal of a

new

particle, where in reality there is none. If the modelling of the

background

was perfect, and the number of events observed was sufficiently large

that the

impact of random statistical fluctuations was negligible, then this

would be

impossible. But for real experiments, it is necessary to guard against

the

problem of tuning the cuts.

One method that is often used to avoid the danger of tuning the cuts is to

analyse the data "blind": the physicists fix the choice of selection cuts,

and measure or model the background, before they allow themselves to look at

the actual measured data. However this method leaves open the possibility

that the cuts might accidentally be tuned by chance, so that the cuts amplify

the effect of a statistical fluctuation, which could lead the experiment to

report an erroneous result.

A more robust and informative way to avoid the danger of tuning the cuts is to

investigate and report the effect of a range of different cuts. This is the

approach used by the Dubna group in the paper arXiv:1208.3829 that announces

the observation of the E(38) boson. They consider 4 different choices of

cuts, which fall, however, into 2 pairs of similar choices, and for the

deuteron beam on a copper target, where the kinetic energy of each deuteron is

6 GeV = 6000 MeV, they report the measurements for all 4 choices of the cuts.

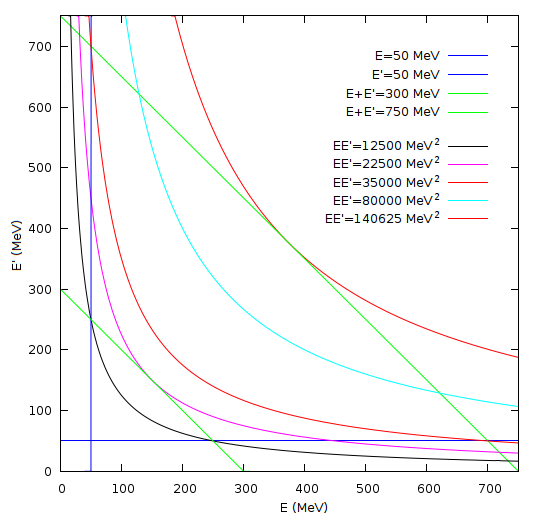

To get a rough understanding of the background distribution of

that results from a particular choice of cuts, I'll consider their

criteria (A), which are the criteria used for the measurements shown in Figure

2(a), which I reproduced above, and for the simulation shown in Figure 11,

which I reproduced above. The cuts in this case are that the energies

that results from a particular choice of cuts, I'll consider their

criteria (A), which are the criteria used for the measurements shown in Figure

2(a), which I reproduced above, and for the simulation shown in Figure 11,

which I reproduced above. The cuts in this case are that the energies  and

and  of the two photons are required to be

of the two photons are required to be

, where the symbol

, where the symbol  means

"greater than"; the sum

means

"greater than"; the sum  of the photon energies is required to

satisfy

of the photon energies is required to

satisfy

, where the symbol

, where the symbol  means "less

than"; and the angle

means "less

than"; and the angle  between the directions of motion of the two

photons is required to satisfy

between the directions of motion of the two

photons is required to satisfy

, which means

that

, which means

that  is required to be not less than about

is required to be not less than about  . Tommaso

suggested that the purpose of the lower limit on

. Tommaso

suggested that the purpose of the lower limit on  might be to ensure

that the two photons are in most cases found in different modules of the

calorimeter.

might be to ensure

that the two photons are in most cases found in different modules of the

calorimeter.

From the diagram on page 1 of the announcement paper arXiv:1208.3829, which

also appears on page 4 of the paper arXiv:0806.2790 which describes the

detector and the method of measuring the background, each of the two arms of

the calorimeter consists of 16 hexagonal modules. From the table on page 5

of arXiv:0806.2790, the total area of the two arms of the detector is

, so the area of one arm of

the detector is

, so the area of one arm of

the detector is

. To

get a rough understanding of the background distribution of

. To

get a rough understanding of the background distribution of

, I'll approximate the right arm of the detector as a circle of this

area. I'll denote the radius of that circle by

, I'll approximate the right arm of the detector as a circle of this

area. I'll denote the radius of that circle by  , so from

, so from

, we have

, we have

, where the symbol

, where the symbol  means

"approximately equal to".

means

"approximately equal to".

From page 3 of arXiv:0806.2790, the front surface of the calorimeter is 3

metres from the interaction point, so if one photon passes through the centre

of the calorimeter and the other photon passes through a point on the edge of

its front surface, then we have

, so

, so

and

and

, while if the two photons pass through opposite points on the edge

of the front surface of the calorimeter, we have

, while if the two photons pass through opposite points on the edge

of the front surface of the calorimeter, we have

and

and

.

.

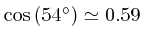

From above, the invariant mass

of the two photons is

of the two photons is

. For fixed energies

. For fixed energies  and

and  of the photons, the largest possible value of

of the photons, the largest possible value of

is obtained when

is obtained when

has its minimum

value of about 0.970, so the largest possible value of

has its minimum

value of about 0.970, so the largest possible value of

is

about

is

about

, and the smallest possible value of

, and the smallest possible value of

is obtained when

is obtained when

has the maximum value 0.997

allowed by the cut, so the smallest possible value of

has the maximum value 0.997

allowed by the cut, so the smallest possible value of

is

about

is

about

.

.

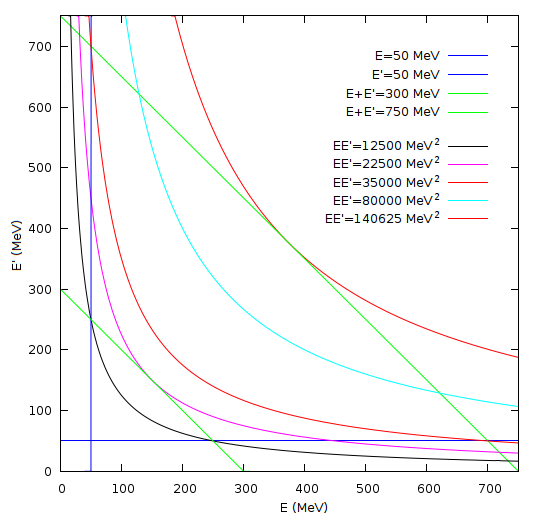

This diagram shows the cuts on  and

and  for the criteria (A), with

for the criteria (A), with  plotted in the horizontal direction and

plotted in the horizontal direction and  plotted in the vertical

direction. The allowed values of

plotted in the vertical

direction. The allowed values of

lie within the

trapezium-shaped region whose boundaries are the green straight line running

from the top left corner to the bottom right corner of the diagram, which

corresponds to

lie within the

trapezium-shaped region whose boundaries are the green straight line running

from the top left corner to the bottom right corner of the diagram, which

corresponds to

, the

green straight line parallel to that one, which corresponds to

, the

green straight line parallel to that one, which corresponds to

, the vertical blue straight line,

which corresponds to

, the vertical blue straight line,

which corresponds to

, and

the horizontal blue straight line, which corresponds to

, and

the horizontal blue straight line, which corresponds to

. The five curved lines are

examples of lines on which the product

. The five curved lines are

examples of lines on which the product  has a constant value. The

smallest value of

has a constant value. The

smallest value of  attainable in the trapezium-shaped region of allowed

values of

attainable in the trapezium-shaped region of allowed

values of

corresponds to the black curve,

corresponds to the black curve,

, which intersects the allowed

region at the points

, which intersects the allowed

region at the points

and

and

. So the smallest possible

value of

. So the smallest possible

value of

for the cut criteria (A) is about

for the cut criteria (A) is about

, which is roughly in agreement with

Figures 2(a) and 11, that I reproduced above and above. The largest attainable value

of

, which is roughly in agreement with

Figures 2(a) and 11, that I reproduced above and above. The largest attainable value

of  corresponds to the upper red curve,

corresponds to the upper red curve,

, so the largest possible

value of

, so the largest possible

value of

for the cut criteria (A) is about

for the cut criteria (A) is about

, which is again roughly in agreement

with Figures 2(a) and 11.

, which is again roughly in agreement

with Figures 2(a) and 11.

As Tommaso pointed out, it is also important to understand the normalization

of the background distribution, which is the overall scale factor applied to

the background distribution once its shape is known. To address this

requirement, the Dubna physicists used two different normalizations of the

background distribution for each set of cut criteria. The first choice of

background normalization, used in Figures 2(a), 3(a), 4(a), 5(a), 6(a), 7(a),

and 10(a), set the total number of background photon pairs equal to the total

number of observed photon pairs, which due to the excesses above background in

the region of

, resulted in the observed

distribution of photon pairs falling below the background for some intervals

of

, resulted in the observed

distribution of photon pairs falling below the background for some intervals

of

. The second choice of background normalization, used

in Figures 2(b), 3(b), 4(b), 5(b), 6(b), 7(b), and 10(b), set the number of

background photon pairs in a range of

. The second choice of background normalization, used

in Figures 2(b), 3(b), 4(b), 5(b), 6(b), 7(b), and 10(b), set the number of

background photon pairs in a range of

away from the excess

around

away from the excess

around

equal to the number of observed photon pairs in that range of

equal to the number of observed photon pairs in that range of

. This method of fixing the background normalization in a "control

region", away from the candidate "signal region", is often used in searches

for new physics at the CERN Large Hadron Collider. The announcement paper

arXiv:1208.3829 found evidence for the E(38) boson for all the processes,

choices of cut criteria, and choices of background normalization for which it

presented measured data.

. This method of fixing the background normalization in a "control

region", away from the candidate "signal region", is often used in searches

for new physics at the CERN Large Hadron Collider. The announcement paper

arXiv:1208.3829 found evidence for the E(38) boson for all the processes,

choices of cut criteria, and choices of background normalization for which it

presented measured data.

By using well-known properties of bremsstrahlung, I used the Dubna

measurements to estimate the coupling constant of the up and down quarks to

the E(38) boson candidate as roughly  in order of magnitude, if the

E(38) is produced in a bremsstrahlung-like manner and decays only to two

photons. The details are here.

For comparison, the coupling constants of electrons, up quarks, and

down quarks to photons, in the same units, are about

in order of magnitude, if the

E(38) is produced in a bremsstrahlung-like manner and decays only to two

photons. The details are here.

For comparison, the coupling constants of electrons, up quarks, and

down quarks to photons, in the same units, are about  ,

,  , and

, and  respectively. The small magnitude of the coupling constant of the up

and down quarks to the E(38), and the presumed equally small or smaller

coupling constant of electrons to the E(38), would explain why the existence

of the E(38) was not suspected until it was proposed last year by Eef van

Beveren and George Rupp in arXiv:1102.1863. The coupling constant of the up

and down quarks to the E(38) could be substantially larger in magnitude than

respectively. The small magnitude of the coupling constant of the up

and down quarks to the E(38), and the presumed equally small or smaller

coupling constant of electrons to the E(38), would explain why the existence

of the E(38) was not suspected until it was proposed last year by Eef van

Beveren and George Rupp in arXiv:1102.1863. The coupling constant of the up

and down quarks to the E(38) could be substantially larger in magnitude than

if, for example, the E(38) decayed mainly to pairs of sufficiently

light particles of dark matter, so that only a small fraction of the E(38)'s

produced in the Dubna experiment decayed to pairs of photons.

if, for example, the E(38) decayed mainly to pairs of sufficiently

light particles of dark matter, so that only a small fraction of the E(38)'s

produced in the Dubna experiment decayed to pairs of photons.

The up and down quarks are the main quark constituents of protons and neutrons: a

proton consists of two up quarks plus a down quark plus an indeterminate

number of quark-antiquark pairs and gluons, and a neutron consists of an up

quark plus two down quarks plus an indeterminate number of quark-antiquark

pairs and gluons.

Quarks are similar to electrons, except for the fact that they can emit

and absorb gluons. Gluons are similar to photons, except for the fact

that they can themselves emit and absorb other gluons. The quarks and

gluons interact so strongly with each other that an isolated quark or

gluon can never be separated from other quarks or antiquarks and gluons

by a distance of more than about 10-15 metres.

Quarks and gluons can be indirectly "seen" in high energy physics

experiments such as the ATLAS and CMS experiments at the Large Hadron

Collider at CERN, because a near head-on collision between a quark,

antiquark, or gluon in a proton going in one direction around the

accelerator ring and a quark, antiquark, or gluon in a proton going in

the other direction around the accelerator ring results in those quarks,

antiquarks, or gluons flying out of the protons that contained them, in

directions that can be up to 90° from the beam direction. As they fly

out of the proton that contained them, these quarks, antiquarks, or

gluons rapidly emit more quarks, antiquarks, and gluons, in a process

similar to bremsstrahlung, and these emitted quarks, antiquarks, and

gluons in turn emit more, so that a cascade of emitted quarks,

antiquarks, and gluons builds up. The quarks, antiquarks, and gluons in

such a cascade rapidly assemble themselves into particles such as pions,

protons, and neutrons, which are seen in the detector as a "jet" of

particles of this type, whose total energy and momentum match the energy

and momentum of the quark, antiquark, or gluon that the jet originated

from.

The software on this website is licensed for use under the

Free Software Foundation

General Public

License.

Page last updated 30 November 2020.

Copyright (c) Chris Austin 2012 - 2020.

Privacy policy

The lower panel shows the

excess after subtraction of the Standard Model background. The statistical

significance of the excess above background centred at about 38 MeV is about 5

sigma, which is the usual standard for discovery of a new particle in high

energy physics.

The lower panel shows the

excess after subtraction of the Standard Model background. The statistical

significance of the excess above background centred at about 38 MeV is about 5

sigma, which is the usual standard for discovery of a new particle in high

energy physics.