| Home | Blog index | Previous | Next | About | Privacy policy |

By Chris Austin. 26 November 2020.

An earlier version of this post was published on another website on 26 July 2012.

Hello, and welcome to this blog. I am Chris Austin, I work independently on high energy physics theory, in Maryport on the north-west coast of England, UK.

In this series of posts, I would like to tell you something about the foundation of our understanding of the way the physical world works, which I'll call Dirac-Feynman-Berezin sums.

I'll show you some formulae and things like that along the way, but I'll try to explain what all the parts mean as we go along, so you don't need to know about that sort of thing in advance.

First I have to tell you about action.

About 60 years after Sir Isaac Newton published his laws of motion in 1687, Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis discovered that Newton's laws follow from the requirement that a quantity he called "action", that depends on the positions and motions of a collection of objects over a period of time, should be relatively unaltered by small changes in the positions and motions of those objects.

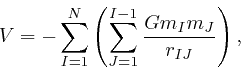

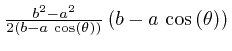

For an example, let's consider a collection of objects, such that each object

behaves approximately as though its mass is concentrated at a single point,

the objects are moving slowly compared to the speed of light, and the forces

between the objects arise from a contribution to their total energy, called

their potential energy ![]() , that depends on their positions but not on their

motions. This is a useful first approximation for many things in the

everyday world, for the Sun and the planets in the Solar System, for the

motions of most of the stars in our galaxy, and for the atoms in a solid,

liquid, gas, or living thing.

, that depends on their positions but not on their

motions. This is a useful first approximation for many things in the

everyday world, for the Sun and the planets in the Solar System, for the

motions of most of the stars in our galaxy, and for the atoms in a solid,

liquid, gas, or living thing.

If ![]() denotes the sum of the kinetic energies of the objects, or in other

words, the energy due to their motion, where the kinetic energy of a pointlike

object of mass

denotes the sum of the kinetic energies of the objects, or in other

words, the energy due to their motion, where the kinetic energy of a pointlike

object of mass ![]() moving at a speed

moving at a speed ![]() is

is

![]() if

if ![]() is small

compared to the speed of light, then the formula for the action of the objects

over a period of time that begins at

is small

compared to the speed of light, then the formula for the action of the objects

over a period of time that begins at ![]() and ends at

and ends at ![]() is:

is:

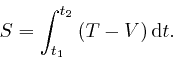

means that

means that We can specify the position of an object at a particular moment in time by 3 numbers, called coordinates. For example, we can specify the position of an aeroplane by its latitude and longitude, in degrees, and its altitude, in meters. We can write these 3 numbers as a list, for example (latitude, longitude, altitude).

If the number of objects in our example is ![]() , then their positions, at a

particular moment in time, can be specified by a table of numbers with 3

columns and

, then their positions, at a

particular moment in time, can be specified by a table of numbers with 3

columns and ![]() rows. Each row gives the coordinates of a different one of the

objects. The motions of the

rows. Each row gives the coordinates of a different one of the

objects. The motions of the ![]() objects over a period of time can be

represented as accurately as desired by a series of such tables, one for each

of a closely spaced sequence of moments in time.

objects over a period of time can be

represented as accurately as desired by a series of such tables, one for each

of a closely spaced sequence of moments in time.

It is convenient to let a single symbol, say ![]() , represent this entire

collection of data. Then if the letter

, represent this entire

collection of data. Then if the letter ![]() , for example, represents one of

the numbers 1, 2, 3, and the letter

, for example, represents one of

the numbers 1, 2, 3, and the letter ![]() , for example, represents one of the

numbers

, for example, represents one of the

numbers

![]() , the value of position coordinate number

, the value of position coordinate number ![]() , of

object number

, of

object number ![]() , at time

, at time ![]() , can be represented as

, can be represented as ![]() , where the

subscripts

, where the

subscripts ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() are called indexes. Alternative notations for

the same thing, which can be used as convenient, are

are called indexes. Alternative notations for

the same thing, which can be used as convenient, are

![]() , and

, and

![]() , for example.

, for example.

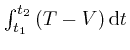

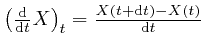

The speed ![]() of an object is proportional to the rate at which its

coordinates change with time. If a collection of data that gives the value

of a quantity at each moment in time is represented by a symbol or expression

of an object is proportional to the rate at which its

coordinates change with time. If a collection of data that gives the value

of a quantity at each moment in time is represented by a symbol or expression

![]() , then the collection of data that gives the rate of change of that

quantity with time, at each moment in time, is often represented as

, then the collection of data that gives the rate of change of that

quantity with time, at each moment in time, is often represented as

![]() , or alternatively

, or alternatively

![]() . The Leibniz

. The Leibniz ![]() in the

numerator of

in the

numerator of

![]() means, "the change in the

following expression, when the time changes by the tiny amount

means, "the change in the

following expression, when the time changes by the tiny amount ![]() ," and indicates that the formula is to be taken in the limit where the

size of the time interval

," and indicates that the formula is to be taken in the limit where the

size of the time interval ![]() tends to 0. The value of

tends to 0. The value of

![]() at time

at time ![]() is

is

, which is well-defined if

, which is well-defined if ![]() changes

smoothly with

changes

smoothly with ![]() . The coordinates

. The coordinates ![]() of the objects in our example

will change smoothly with

of the objects in our example

will change smoothly with ![]() for a sensible choice of position coordinates,

since we assumed that

for a sensible choice of position coordinates,

since we assumed that ![]() is small compared to the speed of light, and thus

finite.

is small compared to the speed of light, and thus

finite.

To calculate the speed ![]() of object number

of object number ![]() , we need to know to the

distance travelled for a small change in its coordinates

, we need to know to the

distance travelled for a small change in its coordinates ![]() . For

example the distance travelled by an aeroplane, for a

. For

example the distance travelled by an aeroplane, for a ![]() change in

its longitude at fixed latitude and altitude, is smaller, the closer the

aeroplane is to the north or south pole.

change in

its longitude at fixed latitude and altitude, is smaller, the closer the

aeroplane is to the north or south pole.

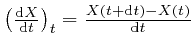

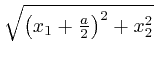

For the flat 2-dimensional world of Euclidean geometry, we can choose as

coordinates the distances from 2 fixed straight lines, at right-angles to one

another. These coordinates were introduced by

René Descartes,

and are called

Cartesian coordinates. The distance ![]() between two points whose

between two points whose ![]() coordinates differ by

coordinates differ by ![]() and whose

and whose ![]() coordinates differ by

coordinates differ by ![]() is then

given by Pythagoras as

is then

given by Pythagoras as

![]() , since directly from the

diagram,

, since directly from the

diagram,

![]() .

.

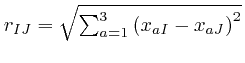

For the flat 3-dimensional generalization of Euclidean geometry, called

3-dimensional Euclidean space, we can choose as coordinates the distances from

3 fixed flat planes, each at right-angles to the other two. These are also

called Cartesian coordinates. The distance ![]() between two points whose

between two points whose

![]() coordinates differ by

coordinates differ by ![]() , for

, for ![]() and

and ![]() , is then

, is then

![]() , which follows from applying Pythagoras first to

the

, which follows from applying Pythagoras first to

the ![]() and

and ![]() coordinates, and then to

coordinates, and then to

![]() and

and ![]() .

.

The assumptions of our example imply that any gravitational fields present are

sufficiently weak that if we use Cartesian coordinates, then distances are

given by Pythagoras to a good approximation, for otherwise the objects would

not continue to move slowly compared to the speed of light. Then in

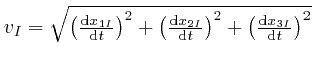

Cartesian coordinates, the speed ![]() of object number

of object number ![]() is

is

, and the sum of the kinetic energies of the

objects is given by:

, and the sum of the kinetic energies of the

objects is given by:

The symbol ![]() is the upper-case Greek letter Sigma, and indicates a sum of

what follows it. The idea is that each contribution to the sum is obtained

from the expression that follows the

is the upper-case Greek letter Sigma, and indicates a sum of

what follows it. The idea is that each contribution to the sum is obtained

from the expression that follows the ![]() , by substituting a specific value

for one of the indexes in the expression, and the notations below and above

the

, by substituting a specific value

for one of the indexes in the expression, and the notations below and above

the ![]() show which index is to be substituted, and the range of values of

that index, for which terms are to be included in the sum. Thus the meaning

of

show which index is to be substituted, and the range of values of

that index, for which terms are to be included in the sum. Thus the meaning

of ![]() is quite similar to the meaning of

is quite similar to the meaning of ![]() as above. The difference is that

as above. The difference is that

![]() is used for a sum over a discrete index such as

is used for a sum over a discrete index such as ![]() or

or ![]() , while

, while

![]() , together with a tiny factor such as

, together with a tiny factor such as ![]() , is used for a sum

over a continuous index such as

, is used for a sum

over a continuous index such as ![]() .

.

Let's now consider a small change to the positions and motions of the ![]() objects during the period of time from

objects during the period of time from ![]() to

to ![]() . I'll represent the

change, or "perturbation", of the positions and motions by the Greek letter

. I'll represent the

change, or "perturbation", of the positions and motions by the Greek letter

![]() , pronounced epsilon, which is often used to represent a small

quantity, so the modified positions and motions are represented by

, pronounced epsilon, which is often used to represent a small

quantity, so the modified positions and motions are represented by

![]() . Here

. Here ![]() , like

, like ![]() , represents an entire collection

of data, for example it could introduce different types of wobbles to the

motions of each of the objects. I shall assume that

, represents an entire collection

of data, for example it could introduce different types of wobbles to the

motions of each of the objects. I shall assume that ![]() is 0 at

is 0 at

![]() and

and ![]() , or in other words, that

, or in other words, that

![]() for all values

for all values ![]() of

of ![]() and all values

and all values

![]() of

of ![]() , while for times

, while for times ![]() between

between ![]() and

and

![]() , I shall assume only that all the

, I shall assume only that all the

![]() are small, and

change smoothly with time.

are small, and

change smoothly with time.

Near the start of the post, above,

I said that de Maupertuis's requirement, which

implies Newton's laws, is that the action should be relatively unaltered by

small changes to the positions and motions of the objects. What I meant by

that is that as ![]() tends to 0, or in other words, as

tends to 0, or in other words, as

![]() approaches 0 for all relevant values of

approaches 0 for all relevant values of ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and

![]() , the change to the action should tend to 0 more rapidly than in proportion

to

, the change to the action should tend to 0 more rapidly than in proportion

to ![]() .

.

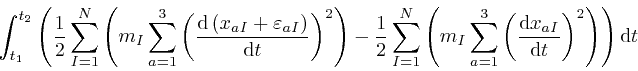

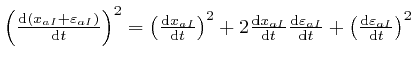

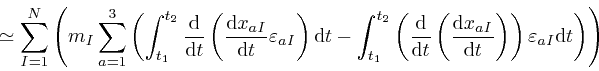

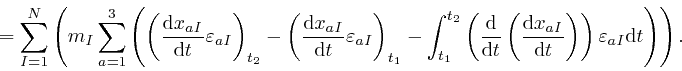

The change to the contribution

to the

action, that results from the replacement of

to the

action, that results from the replacement of ![]() by

by

![]() , is:

, is:

, and the contribution from the first expression,

usually called a term, in the right-hand side of this, cancels against the

last expression in the left-hand side of the above equation for each value of

the indexes

, and the contribution from the first expression,

usually called a term, in the right-hand side of this, cancels against the

last expression in the left-hand side of the above equation for each value of

the indexes

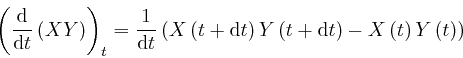

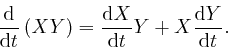

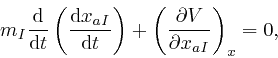

Let's now consider the rate of change with time of a product ![]() , where

, where

![]() and

and ![]() represent collections of data that give the values, at each moment

in time, of quantities that change smoothly with time. The expression

represent collections of data that give the values, at each moment

in time, of quantities that change smoothly with time. The expression ![]() represents the collection of data that gives the value of the product

represents the collection of data that gives the value of the product ![]() at each moment in time, so from above, the collection of data that gives

the rate of change with time of the product

at each moment in time, so from above, the collection of data that gives

the rate of change with time of the product ![]() , at each moment in time,

can be represented as

, at each moment in time,

can be represented as

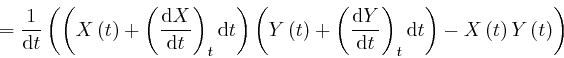

![]() . And:

. And:

, we have

, we have

is 0 in the limit where

is 0 in the limit where

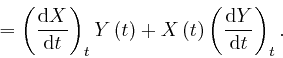

The above formula is true at every value of the time ![]() , so it can be

summarized as:

, so it can be

summarized as:

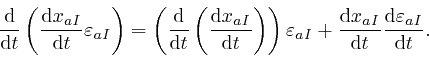

Applying this to the product

![]() , we have:

, we have:

that results from the replacement of

that results from the replacement of

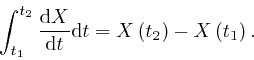

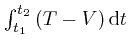

Let's now consider the expression

, where

, where ![]() is any time-dependent quantity whose

value

is any time-dependent quantity whose

value ![]() changes smoothly with time. From the description I gave near the

start of the post above,

this expression is given by dividing the period from

changes smoothly with time. From the description I gave near the

start of the post above,

this expression is given by dividing the period from ![]() to

to ![]() up into a great number of tiny time intervals, each so small that

up into a great number of tiny time intervals, each so small that

![]() only changes by a tiny amount during any

one time interval, and adding together a contribution from each of these tiny

time intervals. The contribution from a tiny time interval of length

only changes by a tiny amount during any

one time interval, and adding together a contribution from each of these tiny

time intervals. The contribution from a tiny time interval of length

![]() is

is

![]() , where

, where

![]() is evaluated at an arbitrary moment during

that interval, and the expression is the limit of the sum of all the

contributions, as the period is divided up so finely that the length of the

longest tiny interval tends to 0.

is evaluated at an arbitrary moment during

that interval, and the expression is the limit of the sum of all the

contributions, as the period is divided up so finely that the length of the

longest tiny interval tends to 0.

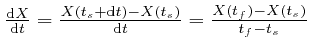

For a tiny time interval that starts at time ![]() and finishes at time

and finishes at time ![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() , we have

, we have

in the

limit where

in the

limit where ![]() tends to 0, so the contribution of that interval is

tends to 0, so the contribution of that interval is

![]() . When

we add together the contributions of all the tiny

intervals, the

. When

we add together the contributions of all the tiny

intervals, the

![]() term in the contribution of each

interval except the last one cancels the

term in the contribution of each

interval except the last one cancels the

![]() term in the

contribution of next interval, so that:

term in the

contribution of next interval, so that:

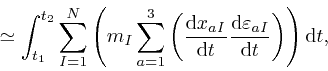

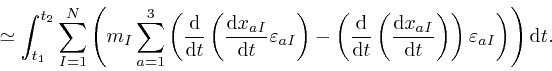

This is true, in particular, if ![]() is

is

![]() , so from the previous result, the change to

, so from the previous result, the change to

that results from the replacement of

that results from the replacement of ![]() by

by

![]() , is:

, is:

that

results from the replacement of

that

results from the replacement of

, where

, where

is

the distance between object

is

the distance between object

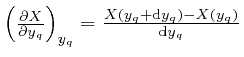

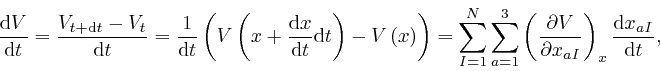

If

a quantity, such as the potential energy, depends on a number of quantities

![]() that can vary continuously, where

that can vary continuously, where ![]() represents the collection of those

quantities, and the index

represents the collection of those

quantities, and the index ![]() distinguishes the quantities in the collection,

and if the collection of data that gives the value of the dependent quantity

at each

distinguishes the quantities in the collection,

and if the collection of data that gives the value of the dependent quantity

at each ![]() , or in other words, at each set of values of the quantities

, or in other words, at each set of values of the quantities ![]() ,

is represented by a symbol

,

is represented by a symbol ![]() , then the collection of data that gives the

rate of change of the dependent quantity as the quantity

, then the collection of data that gives the

rate of change of the dependent quantity as the quantity ![]() changes, while

all the other quantities in

changes, while

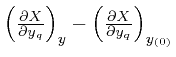

all the other quantities in ![]() have fixed values, is usually represented as

have fixed values, is usually represented as

![]() , or alternatively as

, or alternatively as

![]() . The symbol

. The symbol ![]() is an alternative

notation for Leibniz's

is an alternative

notation for Leibniz's ![]() , and

, and

, where the quantities in the collection

, where the quantities in the collection ![]() other than

other than ![]() all have the same values in both terms in the numerator in

the right-hand side as they have in the left-hand side, so their values don't

need to be displayed.

all have the same values in both terms in the numerator in

the right-hand side as they have in the left-hand side, so their values don't

need to be displayed.

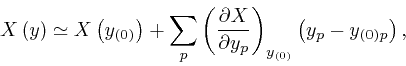

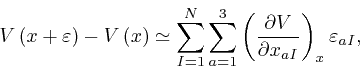

If the value

![]() changes smoothly with

changes smoothly with ![]() , or in other

words, smoothly with the quantities

, or in other

words, smoothly with the quantities ![]() in the collection

in the collection ![]() , then for

, then for ![]() near a reference collection

near a reference collection

![]() , in the sense that all the

quantities

, in the sense that all the

quantities

![]() are small in magnitude, the value

are small in magnitude, the value

![]() can be represented approximately as:

can be represented approximately as:

, where

, where  for all

for all  tend to 0 at least as fast as the

differences

tend to 0 at least as fast as the

differences

Applying

the above formula to the potential energy, with

![]() taken as

taken as ![]() , and

, and

![]() taken as

taken as ![]() ,

we have:

,

we have:

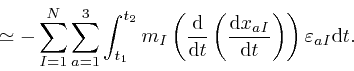

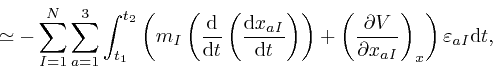

Combining this formula for the change of the potential energy with the formula

for the change of the kinetic energy we obtained

before it, we find that the

change to the action

that

results from the replacement of

that

results from the replacement of ![]() by

by

![]() , is:

, is:

De Maupertuis's principle requires that the change to the action should tend

to 0 more rapidly than in proportion to ![]() , as

, as ![]() tends

to 0. But from the above formula, this is only possible for all

perturbations

tends

to 0. But from the above formula, this is only possible for all

perturbations ![]() such that

such that ![]() is 0 at

is 0 at ![]() and

and ![]() ,

and all the

,

and all the

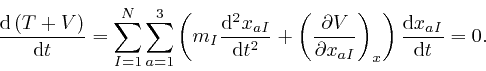

![]() change smoothly with time, if:

change smoothly with time, if:

We are using Cartesian coordinates, so

![]() is the

is the ![]() 'th component of the velocity of the

'th component of the velocity of the ![]() 'th object, and

'th object, and

![]() , which is usually written as

, which is usually written as

, is the

, is the ![]() 'th component of the acceleration of the

'th component of the acceleration of the

![]() 'th object. And by the definition of potential energy, the

'th object. And by the definition of potential energy, the ![]() 'th

component of the force on the

'th

component of the force on the ![]() 'th object is

'th object is

![]() . Thus the above equation is Newton's second law of motion.

. Thus the above equation is Newton's second law of motion.

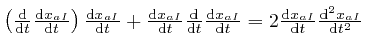

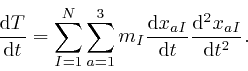

Let's now consider the rate of change with time of the total energy ![]() ,

when the objects move in accordance with Newton's second law of motion, which

we have just derived from de Maupertuis's principle. From Leibniz's rule for

the rate of change of a product, which we proved above,

the rate of change of

,

when the objects move in accordance with Newton's second law of motion, which

we have just derived from de Maupertuis's principle. From Leibniz's rule for

the rate of change of a product, which we proved above,

the rate of change of

is

is

, so the rate of change with time

of the kinetic energy

, so the rate of change with time

of the kinetic energy ![]() is:

is:

From

the sum of the above two formulae, we obtain the rate of change with time

of the total energy ![]() of the objects, when they move in accordance with

Newton's second law of motion, as:

of the objects, when they move in accordance with

Newton's second law of motion, as:

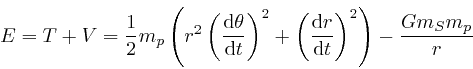

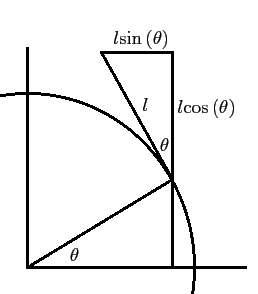

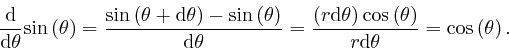

To illustrate the practical application of de Maupertuis's discovery, which is

sometimes called the principle of stationary action, let's consider a planet

in orbit around the Sun, neglecting the gravitational effects of the other

planets, which are relatively small. The mass ![]() of the Sun is much

greater than the mass

of the Sun is much

greater than the mass ![]() of the planet, so to a good approximation, we can

treat the Sun as fixed in position, and just consider the motion of the planet

around the Sun. The gravitational force on the planet is always in the

direction of the straight line from the planet to the Sun, so the planet stays

in the 2-dimensional plane defined by the straight line from the planet's

initial position to the Sun, and the direction of the planet's initial

velocity, which I shall assume is not exactly along that line.

of the planet, so to a good approximation, we can

treat the Sun as fixed in position, and just consider the motion of the planet

around the Sun. The gravitational force on the planet is always in the

direction of the straight line from the planet to the Sun, so the planet stays

in the 2-dimensional plane defined by the straight line from the planet's

initial position to the Sun, and the direction of the planet's initial

velocity, which I shall assume is not exactly along that line.

It is convenient to specify the planet's position in this plane by the

distance ![]() from the planet to the Sun, and the angle between the straight

line from the planet to the Sun, and the initial direction of that line. I

shall represent that angle by

from the planet to the Sun, and the angle between the straight

line from the planet to the Sun, and the initial direction of that line. I

shall represent that angle by ![]() , which is the Greek letter theta. To

keep the formulae as simple as possible, the angle

, which is the Greek letter theta. To

keep the formulae as simple as possible, the angle ![]() will be measured

not in degrees but in "radians", where 1 radian is the angle turned through

when something moving along a circular path has travelled a distance along the

circle equal to the radius of the circle. Thus a full

will be measured

not in degrees but in "radians", where 1 radian is the angle turned through

when something moving along a circular path has travelled a distance along the

circle equal to the radius of the circle. Thus a full ![]() rotation

is

rotation

is

![]() radians, and 1 radian is approximately

radians, and 1 radian is approximately

![]() .

.

Due to measuring the angle ![]() in radians, the distance travelled by the

planet when

in radians, the distance travelled by the

planet when ![]() increases by a small amount

increases by a small amount

![]() at fixed

at fixed

![]() is

is

![]() , and in the limit when

, and in the limit when

![]() tends

to 0, this is in the direction perpendicular to the straight line from the

planet to the Sun. Thus the square of the planet's speed can be calculated

from

tends

to 0, this is in the direction perpendicular to the straight line from the

planet to the Sun. Thus the square of the planet's speed can be calculated

from

![]() and

and

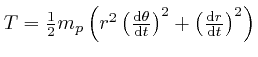

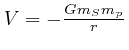

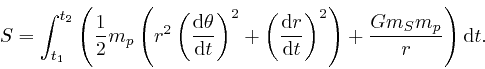

![]() using Pythagoras, so the kinetic energy of the planet is

using Pythagoras, so the kinetic energy of the planet is

. The

gravitational potential energy is

. The

gravitational potential energy is

, so the action

is:

, so the action

is:

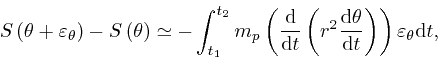

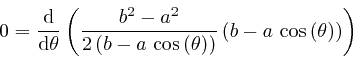

De

Maupertuis's principle requires that the change to the action should tend

to 0 more rapidly than in proportion to

![]() , as

, as

![]() tends to 0. But from the above formula, this is only

possible for all perturbations

tends to 0. But from the above formula, this is only

possible for all perturbations

![]() such that

such that

![]() is 0 at

is 0 at ![]() and

and ![]() , and

, and

![]() changes smoothly with time, if

changes smoothly with time, if

![]() , for all relevant values

of

, for all relevant values

of ![]() . This means that

. This means that

![]() is

independent of time.

is

independent of time.

For a tiny amount of time ![]() , the area swept out by the straight

line from the Sun to the planet during the time interval

, the area swept out by the straight

line from the Sun to the planet during the time interval ![]() is

approximately

is

approximately

![]() , which is the area of the right-angled triangle made by the

straight lines from the Sun to the planet at the times

, which is the area of the right-angled triangle made by the

straight lines from the Sun to the planet at the times ![]() and

and

![]() , together with the straight line tangential to the circle of radius

, together with the straight line tangential to the circle of radius ![]() centred at the Sun, that meets that circle at the position of the planet at

time

centred at the Sun, that meets that circle at the position of the planet at

time ![]() . The difference between

. The difference between

![]() , and the area swept out by the straight

line from the Sun to the planet during the time interval

, and the area swept out by the straight

line from the Sun to the planet during the time interval ![]() , tends

to 0 in proportion to

, tends

to 0 in proportion to

![]() as

as ![]() tends

to 0, and thus more rapidly than in proportion to

tends

to 0, and thus more rapidly than in proportion to ![]() , so the rate

at which the straight line from the Sun to the planet sweeps out area is

, so the rate

at which the straight line from the Sun to the planet sweeps out area is

![]() . We found above

from de Maupertuis's principle that this is independent of time, so the

straight line from the Sun to the planet sweeps out equal areas in equal

times. This is the second of the three laws of planetary motion, which

Johannes Kepler

discovered by studying the astronomical measurements made by

Tycho Brahe.

. We found above

from de Maupertuis's principle that this is independent of time, so the

straight line from the Sun to the planet sweeps out equal areas in equal

times. This is the second of the three laws of planetary motion, which

Johannes Kepler

discovered by studying the astronomical measurements made by

Tycho Brahe.

The product

![]() , which is also

independent of time since the planet's mass

, which is also

independent of time since the planet's mass ![]() is constant, is called the

orbital angular momentum of the planet. I shall represent it by

is constant, is called the

orbital angular momentum of the planet. I shall represent it by ![]() . The

value of

. The

value of ![]() , like the value

, like the value ![]() of the planet's total energy, partly

characterizes the orbit of the planet.

of the planet's total energy, partly

characterizes the orbit of the planet.

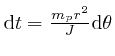

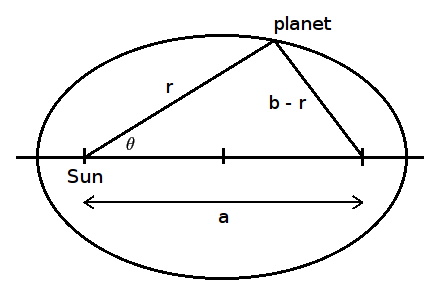

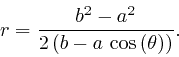

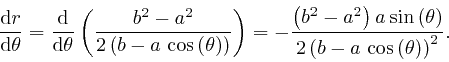

To find the possible shapes of the planet's orbit, we can convert the rate of

change of ![]() with time to the rate of change of

with time to the rate of change of ![]() with

with ![]() , using the

relation

, using the

relation

![]() . The time

interval during which

. The time

interval during which ![]() changes by a tiny amount

changes by a tiny amount

![]() is

is

, so

, so

![]() .

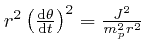

Using this result and also the relation

.

Using this result and also the relation

in the above formula

for the planet's total energy

in the above formula

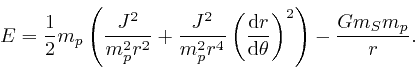

for the planet's total energy ![]() , we find:

, we find:

Rearranging this formula, we find:

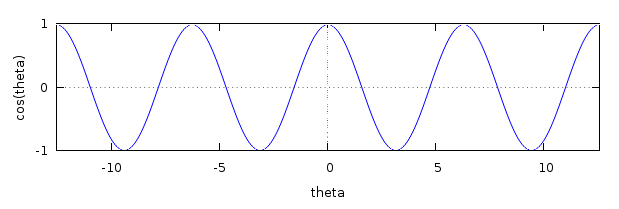

To use this formula to find the possible orbits of the planet, it is helpful

to know about the Cartesian coordinates of something moving around a circle,

and their rate of change with angle. If

something is moving along a circular

path, and ![]() is the angle in radians,

as above, between the straight line from

the centre of the moving object to the centre of the circle, and a fixed

straight line in the plane of the circle though the centre of the circle, then

the traditional names for the Cartesian coordinates of the centre of the

moving object, relative to the centre of the circle, in units of the radius of

the circle, are

is the angle in radians,

as above, between the straight line from

the centre of the moving object to the centre of the circle, and a fixed

straight line in the plane of the circle though the centre of the circle, then

the traditional names for the Cartesian coordinates of the centre of the

moving object, relative to the centre of the circle, in units of the radius of

the circle, are

![]() for the coordinate

parallel to the fixed straight line, and

for the coordinate

parallel to the fixed straight line, and

![]() for the coordinate perpendicular to the fixed straight line in the plane of

the circle. The directions of the coordinates are chosen so that

for the coordinate perpendicular to the fixed straight line in the plane of

the circle. The directions of the coordinates are chosen so that

![]() and

and

![]() . From Pythagoras, we have

. From Pythagoras, we have

![]() ,

for all

,

for all ![]() .

.

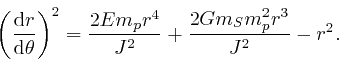

If the object starts at angle ![]() and goes round the circle

and goes round the circle ![]() times, so

that

times, so

that ![]() increases by

increases by ![]() , where

, where ![]() is any whole number, then the

Cartesian coordinates of the centre of the object come back to their initial

values, so that

is any whole number, then the

Cartesian coordinates of the centre of the object come back to their initial

values, so that

![]() , and

, and

![]() , for all whole numbers

, for all whole numbers ![]() . This

diagram shows

. This

diagram shows

![]() , for

, for ![]() in the range

in the range

![]() to

to ![]() .

.

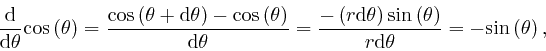

When the angle ![]() increases by a tiny amount

increases by a tiny amount

![]() , the

changes to the coordinates of the centre of the object are approximately the

same as they would be if the object moved a distance

, the

changes to the coordinates of the centre of the object are approximately the

same as they would be if the object moved a distance

![]() along the straight line tangential to the circle at

along the straight line tangential to the circle at ![]() instead of

exactly along the circle, where

instead of

exactly along the circle, where ![]() is the radius of the circle, and the

relative error of this approximation tends to 0 as

is the radius of the circle, and the

relative error of this approximation tends to 0 as

![]() tends

to 0. And from this diagram, the change to the Cartesian coordinate parallel

to the fixed straight line, when the centre of the object moves a distance

tends

to 0. And from this diagram, the change to the Cartesian coordinate parallel

to the fixed straight line, when the centre of the object moves a distance ![]() along the tangential straight line in the direction of increasing

along the tangential straight line in the direction of increasing ![]() , is

, is

![]() , and the change to the Cartesian

coordinate perpendicular to the fixed straight line is

, and the change to the Cartesian

coordinate perpendicular to the fixed straight line is

![]() . Thus:

. Thus:

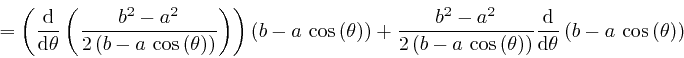

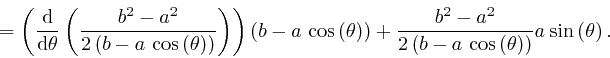

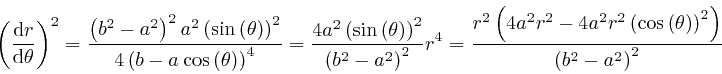

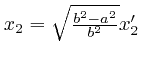

Returning to the planet in orbit around the Sun, we can now confirm that the

above formula for

Returning to the planet in orbit around the Sun, we can now confirm that the

above formula for

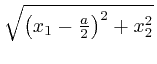

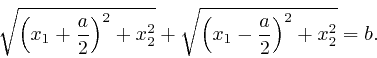

implies that the orbit of the planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one focus,

in agreement with Kepler's first law of planetary motion. An ellipse is the

curve formed by all the points in a plane such that the sum of the distances

from a point on the ellipse to two fixed points, called the focuses of the

ellipse, has a fixed value. With the Sun at one focus, the distance from the

planet to that focus is

implies that the orbit of the planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one focus,

in agreement with Kepler's first law of planetary motion. An ellipse is the

curve formed by all the points in a plane such that the sum of the distances

from a point on the ellipse to two fixed points, called the focuses of the

ellipse, has a fixed value. With the Sun at one focus, the distance from the

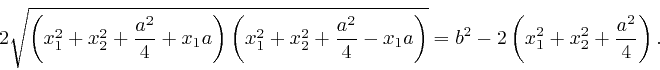

planet to that focus is Rearranging this formula, we find:

is constant, so its rate of change is 0. Thus:

is constant, so its rate of change is 0. Thus:

for the planet's

orbit that we obtained above from de Maupertuis's

principle, we square both sides of the ellipse formula, and then use the

above

relation between

for the planet's

orbit that we obtained above from de Maupertuis's

principle, we square both sides of the ellipse formula, and then use the

above

relation between

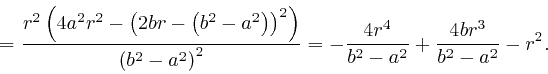

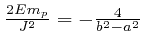

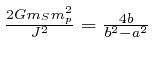

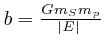

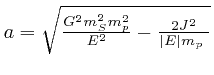

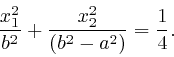

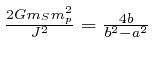

This exactly matches the formula for

for the

planet's orbit that we obtained above from de

Maupertuis's principle, if

for the

planet's orbit that we obtained above from de

Maupertuis's principle, if

and

and

, so that

, so that

, and

, and

, where

, where

![]() denotes the absolute value of

denotes the absolute value of ![]() . The value of

. The value of ![]() is negative because the planet is gravitationally bound to the Sun.

is negative because the planet is gravitationally bound to the Sun.

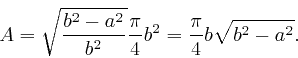

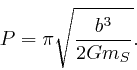

The time taken for the planet to complete one orbit is called the orbital

period, and I shall represent it by ![]() . We found above

that the rate at

which the straight line from the Sun to the planet sweeps out area is

. We found above

that the rate at

which the straight line from the Sun to the planet sweeps out area is

![]() . Thus

. Thus

and

and

by Pythagoras, so the

equation of the ellipse is:

by Pythagoras, so the

equation of the ellipse is:

, it becomes the equation of a circle

of radius

, it becomes the equation of a circle

of radius

, so:

, so:

One of the clues that led to the discovery of Dirac-Feynman-Berezin sums came from the attempted application to electromagnetic radiation of discoveries about heat and temperature. In the next post in this series, Multiple Molecules, we'll look at some of those discoveries.

The software on this website is licensed for use under the Free Software Foundation General Public License.

Page last updated 4 May 2023. Copyright (c) Chris Austin 1997 - 2023. Privacy policy