, is called the natural logarithm of

, is called the natural logarithm of

| Home | Blog index | Previous | Next | About | Privacy policy |

By Chris Austin. 27 November 2020.

An earlier version of this post was published on another website on 7 August 2012.

This is the second in a series of posts about the foundation of our understanding of the way the physical world works, which I am calling Dirac-Feynman-Berezin sums. The first post in the series is Action.

As in the previous post, I'll show you some formulae and things like that along the way, but I'll try to explain what all the parts mean as we go along, if we've not met them already, so you don't need to know about that sort of thing in advance.

One of the clues that led to the discovery of Dirac-Feynman-Berezin sums came from the attempted application to electromagnetic radiation of discoveries about heat and temperature. Today I would like to tell you about some of those discoveries.

Around 60 BC, Titus Lucretius Carus suggested in an epic poem, "On the Nature of Things," that matter consists of indivisible atoms moving incessantly in an otherwise empty void. In 1738 Daniel Bernoulli proposed that the pressure and temperature of gases are consequences of the random motions of large numbers of molecules. The theory was not immediately accepted, but around the middle of the nineteenth century, John James Waterston, August Krönig, Rudolf Clausius, and James Clerk Maxwell discovered that the everyday observations that things tend to have a temperature that can increase or decrease, and that the temperatures of adjacent objects tend to change towards a common intermediate value, follow from the random behaviour of large numbers of microscopic objects subject to Newton's laws, in particular the conservation of total energy.

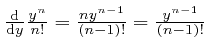

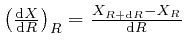

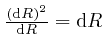

To understand how this happens, it is helpful to know about the rate of change

with ![]() of an expression such as

of an expression such as ![]() , which means

, which means ![]() to the power

to the power ![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is a fixed number greater than 0, and

is a fixed number greater than 0, and ![]() could for example be time

or a position coordinate, measured in units of a fixed amount of time or a

fixed distance.

could for example be time

or a position coordinate, measured in units of a fixed amount of time or a

fixed distance. ![]() does not have to be a whole number, since any number

does not have to be a whole number, since any number ![]() can be approximated as accurately as desired by a ratio of the form

can be approximated as accurately as desired by a ratio of the form

![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() are whole numbers, and

are whole numbers, and

![]() is

the

is

the ![]() 'th power of the

'th power of the ![]() 'th root of

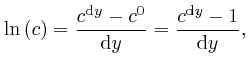

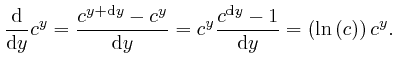

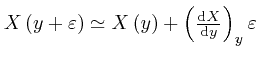

'th root of ![]() . The rate of change with

. The rate of change with ![]() of

of

![]() at

at ![]() , which we can write as

, which we can write as

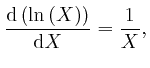

, is called the natural logarithm of

, is called the natural logarithm of ![]() , and usually written

as

, and usually written

as

![]() . It was studied in the sixteenth century

by John Napier. I explained the meaning of an expression like

. It was studied in the sixteenth century

by John Napier. I explained the meaning of an expression like

![]() in the previous post, here.

in the previous post, here.

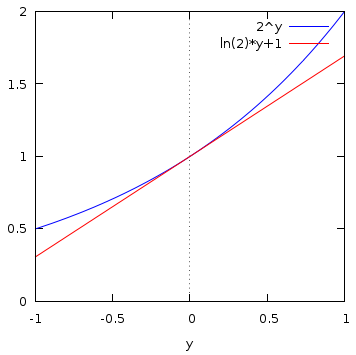

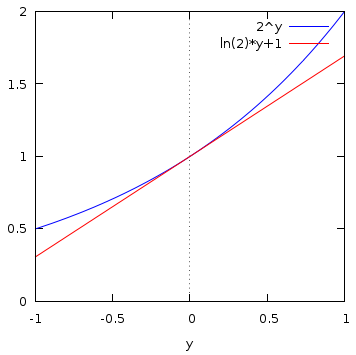

For example, this diagram shows ![]() in blue, for

in blue, for ![]() in the range

in the range ![]() to

1. The red line is the straight line with the same rate of change with

to

1. The red line is the straight line with the same rate of change with ![]() as

as ![]() at

at ![]() , and from its value

, and from its value

![]() at

at ![]() , we can read

from the graph that

, we can read

from the graph that

![]() . The symbol

. The symbol ![]() means, "approximately equal to."

means, "approximately equal to."

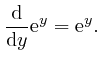

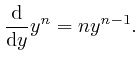

We have:

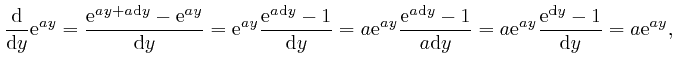

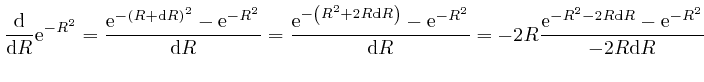

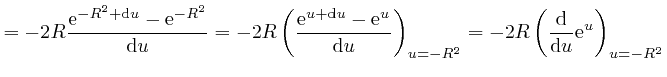

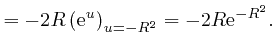

We now find:

The number

![]() such that

such that

![]() is sometimes called Napier's number. From the above formula, we have:

is sometimes called Napier's number. From the above formula, we have:

For any fixed number ![]() , we have:

, we have:

as the tiny quantity

as the tiny quantity

as the tiny quantity

as the tiny quantity

From the above equation with ![]() chosen to be

chosen to be

![]() ,

we find that

,

we find that

for all ![]() , because both these expressions are equal to 1 for

, because both these expressions are equal to 1 for ![]() , and

they both satisfy the equation

, and

they both satisfy the equation

![]() . This equation fixes

. This equation fixes

![]() for all

for all ![]() once

once

![]() is given, because

is given, because

![]() can be calculated from

can be calculated from

![]() as accurately as desired,

by dividing up the interval from 0 to

as accurately as desired,

by dividing up the interval from 0 to ![]() into a great number of sufficiently

tiny intervals, and calculating the approximate value of

into a great number of sufficiently

tiny intervals, and calculating the approximate value of

![]() at the end of each tiny interval from its approximate value at the start of

that interval, by using

at the end of each tiny interval from its approximate value at the start of

that interval, by using

.

.

From the above equation at ![]() , we find that

, we find that

for every number ![]() greater than 0. Thus for any numbers

greater than 0. Thus for any numbers ![]() and

and ![]() , both

greater than 0, we have

, both

greater than 0, we have

![]() . Thus:

. Thus:

If

![]() , so that the symbol

, so that the symbol ![]() , like the expression

, like the expression

![]() , represents the collection of data that gives the value of the

, represents the collection of data that gives the value of the

![]() -dependent quantity

-dependent quantity

![]() at each value of

at each value of ![]() , then from this

formula above, we have

, then from this

formula above, we have

![]() , and from this

formula above, we have

, and from this

formula above, we have

![]() , for all values of

, for all values of

![]() greater than 0. Thus

greater than 0. Thus

![]() , for all

, for all ![]() greater than 0, so:

greater than 0, so:

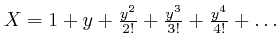

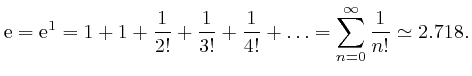

To calculate the value of Napier's number

![]() , we observe first that

for all positive whole numbers

, we observe first that

for all positive whole numbers ![]() :

:

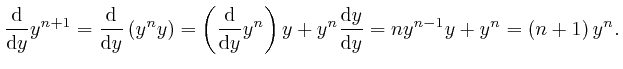

Therefore:

where ![]() is defined to be 1, and for each positive whole number

is defined to be 1, and for each positive whole number ![]() ,

, ![]() is

defined to be the product of all the whole numbers from 1 to

is

defined to be the product of all the whole numbers from 1 to ![]() . The

exclamation mark

. The

exclamation mark ![]() is usually read as "factorial". The

is usually read as "factorial". The ![]() mean

that the sum continues in accordance with the pattern shown by the terms

before the

mean

that the sum continues in accordance with the pattern shown by the terms

before the ![]() . The symbol

. The symbol ![]() is the Greek letter Sigma, and is

called the summation sign. I explained its meaning in the previous

post, here. The symbol

is the Greek letter Sigma, and is

called the summation sign. I explained its meaning in the previous

post, here. The symbol

![]() above the

above the ![]() , which is read as

"infinity", means that the sum is unending.

, which is read as

"infinity", means that the sum is unending.

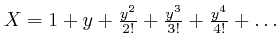

The reason the above formula for

![]() is true is that the sum in the

right-hand side of the formula is equal to 1 for

is true is that the sum in the

right-hand side of the formula is equal to 1 for ![]() , and it satisfies the

same equation

, and it satisfies the

same equation

![]() as

as

![]() does.

So for the same reason as we discussed above, the sum in the right-hand side

of the formula is equal to

does.

So for the same reason as we discussed above, the sum in the right-hand side

of the formula is equal to ![]() , for all

, for all ![]() . The reason the expression

. The reason the expression

satisfies

the equation

satisfies

the equation

![]() is that

is that

![]() on the first term in

on the first term in ![]() gives 0, and

gives 0, and

![]() on each term in

on each term in ![]() after the first gives

the preceding term in

after the first gives

the preceding term in ![]() , since from our observation above,

, since from our observation above,

.

.

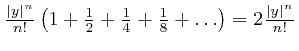

This argument that the expression

satisfies the equation

satisfies the equation

![]() assumes that the endless sum tends to a finite limiting

value as more and more terms are added, no matter how large the magnitude

assumes that the endless sum tends to a finite limiting

value as more and more terms are added, no matter how large the magnitude

![]() of

of ![]() is. In fact, the expression

is. In fact, the expression

![]() increases in magnitude with increasing

increases in magnitude with increasing ![]() for

for

![]() , and

then starts decreasing in magnitude more and more rapidly with increasing

, and

then starts decreasing in magnitude more and more rapidly with increasing ![]() ,

so that the endless sum always does tend to a finite limiting value, no matter

how large

,

so that the endless sum always does tend to a finite limiting value, no matter

how large

![]() is. If

is. If ![]() is larger than

is larger than

![]() ,

then the endless sum of all the terms from

,

then the endless sum of all the terms from

![]() onwards does not

exceed

onwards does not

exceed

in magnitude.

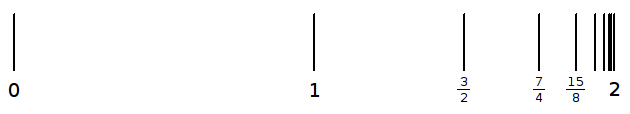

The endless sum

in magnitude.

The endless sum

![]() approaches 2 when it is continued without end, because each successive term

halves the difference between 2 and the sum of the terms up to that point, as

shown in this diagram.

approaches 2 when it is continued without end, because each successive term

halves the difference between 2 and the sum of the terms up to that point, as

shown in this diagram.

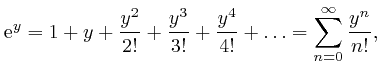

The above formula expressing

![]() as a sum of powers of

as a sum of powers of ![]() is an

example of a "Taylor series," named after Brook Taylor. For

is an

example of a "Taylor series," named after Brook Taylor. For ![]() , it

gives:

, it

gives:

Let's now consider again, as in the previous post, here, the example of a collection of objects, such that

each object behaves approximately as though its mass is concentrated at a

single point, the objects are moving slowly compared to the speed of light,

and the forces between the objects arise from their potential energy ![]() ,

which depends on their positions but not on their motions. We'll continue to

assume that their motions are governed by Newton's laws, and thus by de

Maupertuis's principle of stationary action, which I explained in the previous post, here, and we'll now assume that the

objects are microscopic and their number is very large, so they could be atoms

in solids, liquids, gases, or living things. We'll use the same notation as

in the previous post, here.

,

which depends on their positions but not on their motions. We'll continue to

assume that their motions are governed by Newton's laws, and thus by de

Maupertuis's principle of stationary action, which I explained in the previous post, here, and we'll now assume that the

objects are microscopic and their number is very large, so they could be atoms

in solids, liquids, gases, or living things. We'll use the same notation as

in the previous post, here.

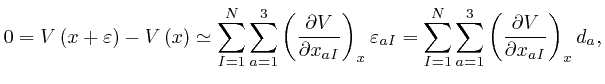

We'll use Cartesian coordinates for the positions of the objects, as we did

when we derived Newton's second law of motion from de Maupertuis's principle, in the previous post, here,

and we'll now assume that the potential energy ![]() depends only on the

relative positions of the objects, as in the example of the gravitational

potential energy, so that the value of

depends only on the

relative positions of the objects, as in the example of the gravitational

potential energy, so that the value of ![]() is unaltered if the positions

is unaltered if the positions ![]() of the objects are shifted by a common displacement

of the objects are shifted by a common displacement ![]() , so that

, so that

![]() , for all

, for all

![]() ,

,

![]() . The symbol

. The symbol ![]() means "less than or equal to."

means "less than or equal to."

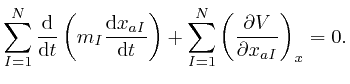

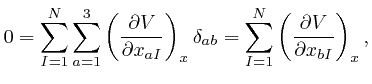

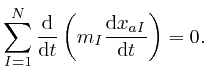

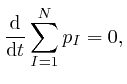

By adding up Newton's second law of motion for the ![]() objects, which we obtained from de Maupertuis's principle in the previous post, here, we find:

objects, which we obtained from de Maupertuis's principle in the previous post, here, we find:

for all the relevant values 1, 2, and 3 of ![]() . Combining this result with

the formula we obtained above by adding up Newton's law of motion for the

. Combining this result with

the formula we obtained above by adding up Newton's law of motion for the ![]() objects, we find:

objects, we find:

The expression

![]() represents the velocity

of the

represents the velocity

of the ![]() 'th object, and the product of an object's mass and its velocity is

called its momentum. I shall let

'th object, and the product of an object's mass and its velocity is

called its momentum. I shall let ![]() represent the collection of data that

gives the momenta of all the objects at each moment in time, so that

represent the collection of data that

gives the momenta of all the objects at each moment in time, so that

![]() for all

for all

![]() ,

,

![]() , and times

, and times ![]() . The above result can then

be written:

. The above result can then

be written:

If the positions and momenta of all the objects are specified at one

particular time, then their values at every other time are determined by

Newton's second law of motion, which we obtained in the previous post,

here, from de Maupertuis's

principle. We'll now divide the range of the possible positions and momenta

of the objects into equal size "bins", and ask what the most likely number

of objects in each bin will be, if the objects are randomly distributed among

the bins, subject to the total energy of the objects having a fixed value ![]() .

.

We'll assume that each bin is sufficiently small that we can treat the

positions and momenta of objects in the same bin as approximately equal to one

another, but also sufficiently large that the number of objects in a typical

bin will be large. For this to be possible, we'll assume that the total

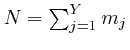

number of objects, ![]() , is very large. This is reasonable for things in the

everyday world, since the number of atoms in a kilogram of matter is in the

range from about

, is very large. This is reasonable for things in the

everyday world, since the number of atoms in a kilogram of matter is in the

range from about ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

We'll allow for the possibility that there could be a number of different

types of object, such that the masses and interactions of objects of the same

type are either identical or very similar to one another, so that the kinetic

energy ![]() and the potential energy

and the potential energy ![]() are either exactly or approximately

unaltered if the positions and momenta of two objects of the same type are

swapped. Objects of different types could be different types of atom, or

atoms of the same type in different situations. For example we'll treat two

oxygen atoms as different types of object if they form parts of gas molecules

contained in separate containers, or if one is part of a gas molecule and the

other is part of the wall of a glass container. We'll assume that the number

of objects of each different type is very large.

are either exactly or approximately

unaltered if the positions and momenta of two objects of the same type are

swapped. Objects of different types could be different types of atom, or

atoms of the same type in different situations. For example we'll treat two

oxygen atoms as different types of object if they form parts of gas molecules

contained in separate containers, or if one is part of a gas molecule and the

other is part of the wall of a glass container. We'll assume that the number

of objects of each different type is very large.

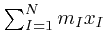

We'll assume that the total momentum of the objects is 0, so that the position

of their centre of mass

is independent of time, and

we'll assume that if any of the objects are parts of liquid or gas molecules,

then some of the other objects form solid containers that prevent the liquids

or gases from spreading without limit. The number of relevant bins is

therefore finite, because the position coordinates of all the objects are

bounded, and the momenta of the objects are also bounded, because we assumed

above that the objects are moving slowly compared to the speed of light. We'll

denote the number of relevant bins by

is independent of time, and

we'll assume that if any of the objects are parts of liquid or gas molecules,

then some of the other objects form solid containers that prevent the liquids

or gases from spreading without limit. The number of relevant bins is

therefore finite, because the position coordinates of all the objects are

bounded, and the momenta of the objects are also bounded, because we assumed

above that the objects are moving slowly compared to the speed of light. We'll

denote the number of relevant bins by ![]() .

.

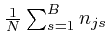

I shall let ![]() represent the collection of data that gives the total number

of objects of each type, so that if

represent the collection of data that gives the total number

of objects of each type, so that if ![]() represents one of the different types

of object, then

represents one of the different types

of object, then ![]() is the total number of objects of type

is the total number of objects of type ![]() , and I shall

let

, and I shall

let ![]() represent the collection of data that gives the number of objects of

each type in each of the bins into which the range of possible positions and

momenta of the objects has been divided, so that if

represent the collection of data that gives the number of objects of

each type in each of the bins into which the range of possible positions and

momenta of the objects has been divided, so that if ![]() represents one of the

bins, then

represents one of the

bins, then ![]() is the number of objects of type

is the number of objects of type ![]() in bin

in bin ![]() .

.

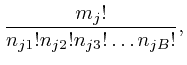

The objects can be distinguished from one another even if they are of the same

type and identical to one another, because we can trace their motions back to

a particular time, and "label" identical objects by the positions and

momenta they had at that time. The number of different assignments of the

![]() objects of type

objects of type ![]() to the bins is

to the bins is ![]() , because each of the

objects can be assigned independently to any of the

, because each of the

objects can be assigned independently to any of the ![]() bins, and of these

bins, and of these

![]() assignments, the number such that

assignments, the number such that ![]() of the objects of type

of the objects of type

![]() are in bin 1,

are in bin 1, ![]() of them are in bin 2, and so on, is:

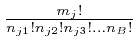

of them are in bin 2, and so on, is:

To understand why the above formula gives the number of different assignments

of the ![]() objects of type

objects of type ![]() to the

to the ![]() bins, such that for each whole

number

bins, such that for each whole

number ![]() in the range 1 to

in the range 1 to ![]() , the number of objects of type

, the number of objects of type ![]() in bin

in bin ![]() is

is ![]() , we note first that the number of different ways of putting

, we note first that the number of different ways of putting ![]() distinguishable objects in

distinguishable objects in ![]() distinguishable places, such that exactly one

object goes to each place, is

distinguishable places, such that exactly one

object goes to each place, is ![]() , because we can put the first object in any

of the

, because we can put the first object in any

of the ![]() places, the second object in any of the remaining

places, the second object in any of the remaining ![]() places,

and so on. So if there were

places,

and so on. So if there were ![]() distinguishable places in bin

distinguishable places in bin ![]() , for

each

, for

each ![]() in the range 1 to

in the range 1 to ![]() , then the number of different ways of putting

the

, then the number of different ways of putting

the ![]() objects in these

objects in these

![]() distinct places would be

distinct places would be ![]() . This overcounts the number of different

assignments of the objects to the bins by a factor

. This overcounts the number of different

assignments of the objects to the bins by a factor

![]() , because we can divide up the

, because we can divide up the ![]() arrangements into

classes, such that arrangements are in the same class if they only differ by

permuting objects within bins. Each class then corresponds to a different

assignment of the objects to the bins. The number of the

arrangements into

classes, such that arrangements are in the same class if they only differ by

permuting objects within bins. Each class then corresponds to a different

assignment of the objects to the bins. The number of the ![]() arrangements in each class is

arrangements in each class is

![]() , so

the number of different classes is

, so

the number of different classes is

.

.

The number of different assignments of all ![]() objects to the

objects to the ![]() bins is

bins is

![]() , and of these, the number such that

, and of these, the number such that ![]() of the objects of type

of the objects of type ![]() are in bin

are in bin ![]() , for all

, for all ![]() and

and ![]() , which I shall denote by

, which I shall denote by ![]() , is the

product of the above number over

, is the

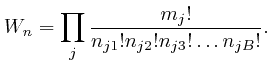

product of the above number over ![]() , which we can write as:

, which we can write as:

The total energy

![]() of the objects, when the numbers of objects of the different types

in the different bins are given by the collection of data

of the objects, when the numbers of objects of the different types

in the different bins are given by the collection of data ![]() , is

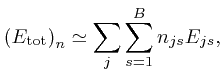

approximately:

, is

approximately:

where ![]() is the energy of an object of type

is the energy of an object of type ![]() in the centre of bin

in the centre of bin

![]() . If we randomly drop the

. If we randomly drop the ![]() objects into the

objects into the ![]() bins, and discard the

result unless the total energy

bins, and discard the

result unless the total energy

![]() differs from

differs from ![]() by at

most a fixed small amount, then the probability that the numbers of objects of

the different types in the different bins are given by

by at

most a fixed small amount, then the probability that the numbers of objects of

the different types in the different bins are given by ![]() is

is ![]() , divided

by the sum of

, divided

by the sum of ![]() over all

over all ![]() such that

such that

![]() is close enough to

is close enough to

![]() . Thus if the objects are randomly distributed among the bins, subject to

the total energy of the objects having a fixed value

. Thus if the objects are randomly distributed among the bins, subject to

the total energy of the objects having a fixed value ![]() , then the most likely

number of objects of each type in each bin will be given by the distribution

, then the most likely

number of objects of each type in each bin will be given by the distribution

![]() for which

for which ![]() reaches its maximum value, among all the distributions

reaches its maximum value, among all the distributions

![]() for which

for which

![]() is approximately equal to

is approximately equal to ![]() .

.

To find the distribution ![]() for which

for which ![]() reaches its maximum value,

subject to

reaches its maximum value,

subject to

![]() , we'll use the observation that the slope of a smooth hill is zero

at the top of the hill. Thus we'll look for the distribution

, we'll use the observation that the slope of a smooth hill is zero

at the top of the hill. Thus we'll look for the distribution ![]() such that

the rate of change of

such that

the rate of change of ![]() with each of the numbers

with each of the numbers ![]() would be 0, if

it were not for the requirement that

would be 0, if

it were not for the requirement that

![]() . For

convenience we'll do the calculation for

. For

convenience we'll do the calculation for

![]() rather than for

rather than for ![]() , so that the product of factors in

, so that the product of factors in ![]() becomes the sum

of the natural logarithms of those factors, due to the result we found above.

This will give the same result for the most likely distribution

becomes the sum

of the natural logarithms of those factors, due to the result we found above.

This will give the same result for the most likely distribution ![]() , because

, because

![]() increases with increasing

increases with increasing ![]() for all

for all

![]() greater than 0, due to the result we found above, so that the

greater than 0, due to the result we found above, so that the ![]() that

gives the largest value of

that

gives the largest value of ![]() will also be the

will also be the ![]() that gives the largest

value of

that gives the largest

value of

![]() .

.

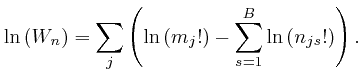

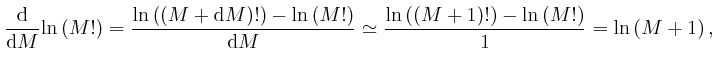

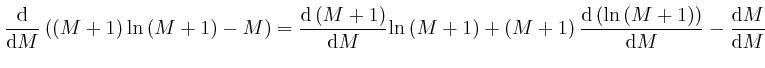

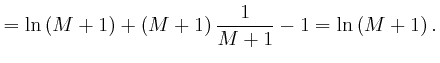

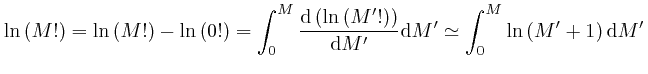

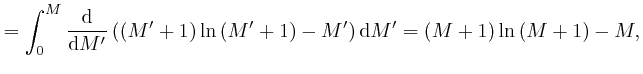

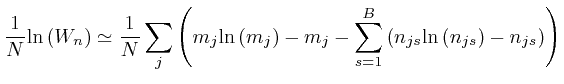

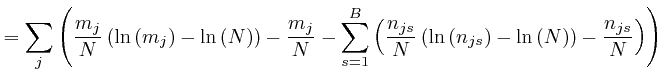

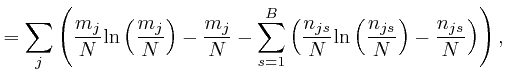

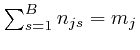

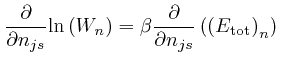

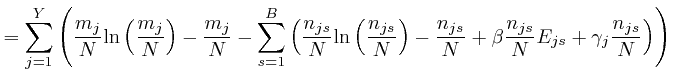

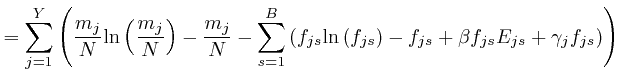

From the formula above for ![]() , we have:

, we have:

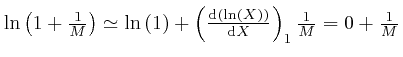

For very large ![]() , we can therefore write:

, we can therefore write:

, for all

, for all  , so the error of the above

approximation decreases in proportion to

, so the error of the above

approximation decreases in proportion to

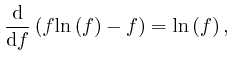

And from

together with Leibniz's rule for the

rate of change of a product, which we obtained in the previous post,

here, we have:

together with Leibniz's rule for the

rate of change of a product, which we obtained in the previous post,

here, we have:

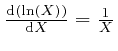

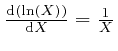

since from above,

![]() and from above,

and from above,

![]() . The above approximation for

. The above approximation for

![]() is in error by an amount that increases slowly for large

is in error by an amount that increases slowly for large ![]() , but its relative

error tends to 0 for large

, but its relative

error tends to 0 for large ![]() , so it is accurate enough to use for finding

the distribution

, so it is accurate enough to use for finding

the distribution ![]() for which

for which ![]() reaches its maximum value, since the

numbers

reaches its maximum value, since the

numbers ![]() will all increase in proportion to the total number of

objects

will all increase in proportion to the total number of

objects ![]() , which we have assumed to be very large. We can also use the

simpler approximation:

, which we have assumed to be very large. We can also use the

simpler approximation:

Thus we have:

, for each type of object

, for each type of object

It is convenient to think of the ratios

![]() as coordinates in

a "space", which I shall call the space of bin fractions, since

as coordinates in

a "space", which I shall call the space of bin fractions, since

![]() is the fraction of the total number of objects

is the fraction of the total number of objects ![]() which are objects

of type

which are objects

of type ![]() in bin

in bin ![]() . The numbers

. The numbers ![]() are restricted to be whole

numbers, but for fixed values of the ratios

are restricted to be whole

numbers, but for fixed values of the ratios

![]() , these numbers

will be proportional to

, these numbers

will be proportional to ![]() , which we have assumed is very large. Thus the

ratios

, which we have assumed is very large. Thus the

ratios

![]() only change by tiny amounts when

only change by tiny amounts when ![]() change

by

change

by ![]() , where the symbol

, where the symbol ![]() means "plus or minus," so since

means "plus or minus," so since

![]() depends smoothly on

depends smoothly on ![]() for all numbers

for all numbers ![]() , we can think of the coordinates

, we can think of the coordinates

![]() as effectively

continuous. If the number of types of object is

as effectively

continuous. If the number of types of object is ![]() , then the space of bin

fractions has

, then the space of bin

fractions has ![]() dimensions, since a point in this space is specified by the

dimensions, since a point in this space is specified by the

![]() numbers

numbers

![]() .

.

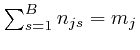

The equation

![]() imposes one relation among the

imposes one relation among the ![]() coordinates of the space of bin

fractions, so it defines a

coordinates of the space of bin

fractions, so it defines a

![]() -dimensional "surface" in

this space. We are looking for the point

-dimensional "surface" in

this space. We are looking for the point ![]() on this surface at which

on this surface at which

![]() reaches the largest value it takes anywhere

on this surface. If we think of

reaches the largest value it takes anywhere

on this surface. If we think of

![]() as the

height of a smooth "hill", then since the slope of a smooth hill is 0 in

each direction at the top of the hill, the rate of change of

as the

height of a smooth "hill", then since the slope of a smooth hill is 0 in

each direction at the top of the hill, the rate of change of

![]() is 0 in each direction along the surface, at the point

is 0 in each direction along the surface, at the point ![]() on the surface where

on the surface where

![]() reaches its maximum

value. However the rate of change of

reaches its maximum

value. However the rate of change of

![]() in

directions that are not along the surface does not have to be 0 at that point.

So we are looking for a point

in

directions that are not along the surface does not have to be 0 at that point.

So we are looking for a point ![]() on the surface such that the rate of

change

on the surface such that the rate of

change

![]() in every direction, whether along the

surface or not, is a multiple of the rate of change of

in every direction, whether along the

surface or not, is a multiple of the rate of change of

![]() in that direction,

since the rate of change of

in that direction,

since the rate of change of

![]() along the surface is

0.

along the surface is

0.

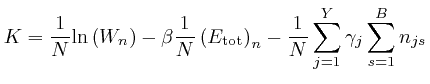

We can do that by looking for a point ![]() for which an expression

for which an expression

The ![]() equations

equations

, one for each type of object

, one for each type of object

![]() , similarly each define a

, similarly each define a

![]() -dimensional surface in

the space of bin fractions, and we'll take these equations into account by

using

-dimensional surface in

the space of bin fractions, and we'll take these equations into account by

using ![]() additional Lagrange multipliers

additional Lagrange multipliers ![]() , one for each of these

equations, where

, one for each of these

equations, where ![]() is the Greek letter gamma. So we'll look for a

point

is the Greek letter gamma. So we'll look for a

point ![]() in the space of bin fractions for which an expression:

in the space of bin fractions for which an expression:

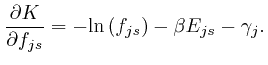

If this is 0 for all ![]() and all

and all ![]() at a point

at a point ![]() in the space of bin

fractions, then the rate of change of

in the space of bin

fractions, then the rate of change of ![]() will be 0 in any direction where the

rates of change of

will be 0 in any direction where the

rates of change of

![]() and all the quantities

and all the quantities

are 0. From the

result we found above, this expression for

are 0. From the

result we found above, this expression for

![]() is 0 when:

is 0 when:

And when the value of each ![]() is given by the above formula, the rate

of change of

is given by the above formula, the rate

of change of

![]() , in any direction

in the space of bin fractions, is

, in any direction

in the space of bin fractions, is ![]() times the rate of change of

times the rate of change of

![]() in

that direction, plus the sum, over the object types

in

that direction, plus the sum, over the object types ![]() , of

, of ![]() times

the rate of change of

times

the rate of change of

in that direction.

in that direction.

Remembering that ![]() and the

and the ![]() are fixed numbers whose values

will be chosen later, we'll now define the value of

are fixed numbers whose values

will be chosen later, we'll now define the value of

![]() , and the

numbers

, and the

numbers

![]() , to be such that the equation

, to be such that the equation

![]() , and

the

, and

the ![]() equations

equations

, are

all satisfied at the point where the value of each

, are

all satisfied at the point where the value of each

![]() is given by the above formula.

is given by the above formula.

For fixed values of

![]() , and the numbers

, and the numbers

![]() , each

of these

, each

of these ![]() equations defines a

equations defines a

![]() -dimensional

surface in the space of bin fractions, and the intersection of these

-dimensional

surface in the space of bin fractions, and the intersection of these ![]() surfaces defines a

surfaces defines a

![]() -dimensional "surface" in the

space of bin fractions. This

-dimensional "surface" in the

space of bin fractions. This

![]() -dimensional surface

is the surface on which the

-dimensional surface

is the surface on which the ![]() equations

equations

![]() and

and

are all satisfied, so

in any direction tangential to this

are all satisfied, so

in any direction tangential to this

![]() -dimensional

surface, the rates of change of

-dimensional

surface, the rates of change of

![]() and

and

are all 0. Thus at the point on this

are all 0. Thus at the point on this

![]() -dimensional surface where the value of each

-dimensional surface where the value of each ![]() is given by

the above formula, the rate of change of

is given by

the above formula, the rate of change of

![]() , in any direction tangential to this

, in any direction tangential to this

![]() -dimensional surface, is 0.

-dimensional surface, is 0.

I'll refer to this

![]() -dimensional surface in the

space of bin fractions as

-dimensional surface in the

space of bin fractions as

![]() , since the fixed

values of

, since the fixed

values of

![]() and the numbers

and the numbers

![]() on it are

determined by the fixed values of

on it are

determined by the fixed values of ![]() and the

and the ![]() . Since the

maximum value of

. Since the

maximum value of ![]() in the region where all

in the region where all ![]() are

are ![]() is attained

when the value of each

is attained

when the value of each ![]() is given by the above formula, and the values

of

is given by the above formula, and the values

of

![]() and the

and the

are all fixed on

are all fixed on

![]() , the maximum value of

, the maximum value of

![]() on

on

![]() , in the region where all

, in the region where all ![]() are

are ![]() , is attained when the value of each

, is attained when the value of each ![]() is given by the

above formula.

is given by the

above formula.

From the formula for

![]() as above, the fixed

values of the

as above, the fixed

values of the ![]() quantities

quantities

![]() and the

and the

![]() are

determined in terms of the

are

determined in terms of the ![]() quantities

quantities ![]() and the

and the ![]() by

the formulae:

by

the formulae:

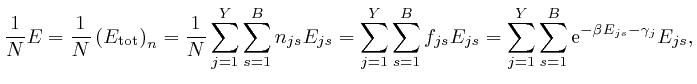

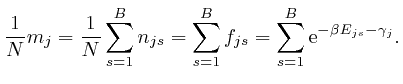

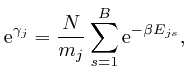

From the last formula above:

so from the formula above:

From above, Napier's number

![]() has the value

has the value

![]() , so if

, so if ![]() was negative, then for a given type of object

was negative, then for a given type of object ![]() ,

,

![]() would be larger for bins for which the energy

would be larger for bins for which the energy ![]() at their

centres is larger, and if

at their

centres is larger, and if ![]() was 0,

was 0, ![]() would be the same for all

bins, no matter how large the energy

would be the same for all

bins, no matter how large the energy ![]() at their centres. In either

of these cases, there would be no justification for our assumption that the

objects are all moving slowly compared to the speed of light, so I'll assume

that

at their centres. In either

of these cases, there would be no justification for our assumption that the

objects are all moving slowly compared to the speed of light, so I'll assume

that ![]() .

.

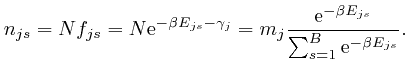

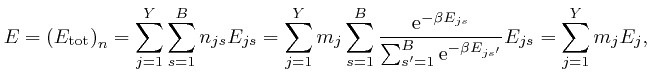

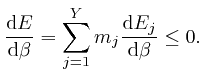

From the above formula for ![]() , we have:

, we have:

where:

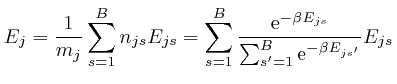

We observe that ![]() is a weighted average of the energies

is a weighted average of the energies ![]() of the

objects of type

of the

objects of type ![]() at the bin centres, such that the relative weights of

larger

at the bin centres, such that the relative weights of

larger ![]() decrease as

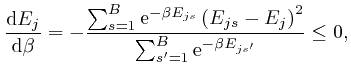

decrease as ![]() increases, so we expect that

increases, so we expect that ![]() will

decrease as

will

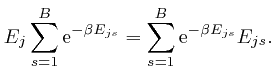

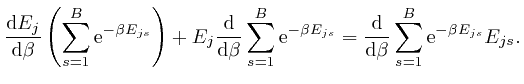

decrease as ![]() increases. To check this, we note that by a

rearrangement of the above formula:

increases. To check this, we note that by a

rearrangement of the above formula:

, and shows that for finite

, and shows that for finite  unless

unless

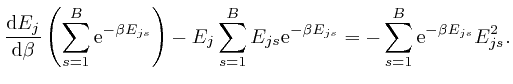

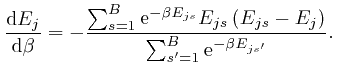

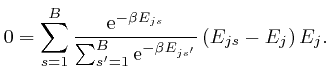

From the formula above for ![]() in terms of the

in terms of the ![]() , we have:

, we have:

If each different assignment of the

objects to the

objects to the

![]() bins, consistent with the given total energy

bins, consistent with the given total energy ![]() of the system, is equally

likely, then as we observed above, the most likely values of the numbers

of the system, is equally

likely, then as we observed above, the most likely values of the numbers ![]() will be those for which

will be those for which ![]() reaches its maximum value, consistent with

the given total energy

reaches its maximum value, consistent with

the given total energy ![]() . If the numbers

. If the numbers ![]() initially differ from

these values, then over the course of time, we expect them to tend towards

these values. The reason for this is that we have assumed that the total

energy can be expressed as a sum of the energies of the individual objects. There will be small corrections to this assumption, due for example to

interactions between gas molecules in the same container, or small mutual

interactions between atoms vibrating near the surfaces of different containers

that are touching one another. These interactions will occur randomly and

can change the numbers

initially differ from

these values, then over the course of time, we expect them to tend towards

these values. The reason for this is that we have assumed that the total

energy can be expressed as a sum of the energies of the individual objects. There will be small corrections to this assumption, due for example to

interactions between gas molecules in the same container, or small mutual

interactions between atoms vibrating near the surfaces of different containers

that are touching one another. These interactions will occur randomly and

can change the numbers

![]() by small amounts such as

by small amounts such as

![]() , so their net effect is that the numbers

, so their net effect is that the numbers ![]() will drift

towards their most likely values.

will drift

towards their most likely values.

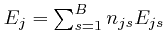

It's convenient, now, to change the meaning of ![]() , which I defined above to be the average energy of an object of type

, which I defined above to be the average energy of an object of type ![]() , to be the total energy of the objects of type

, to be the total energy of the objects of type ![]() , instead.

The total energy

, instead.

The total energy

of the objects of type

of the objects of type

![]() depends on the numbers

depends on the numbers ![]() , so a drift of these numbers with time

can result in a net transfer of energy from one type of object to another,

while the total energy remains constant. If two systems, each of which might

contain a number of different types of object, are initially separated from

one another, with total energies

, so a drift of these numbers with time

can result in a net transfer of energy from one type of object to another,

while the total energy remains constant. If two systems, each of which might

contain a number of different types of object, are initially separated from

one another, with total energies ![]() and

and ![]() and initial values

and initial values ![]() and

and ![]() of

of ![]() , and are brought into contact with one another, such

that neither system exerts any mechanical, electromagnetic, or gravitational

force on the other, but the numbers

, and are brought into contact with one another, such

that neither system exerts any mechanical, electromagnetic, or gravitational

force on the other, but the numbers ![]() for each system can drift due to

random microscopic interactions between parts of the two systems as above, for

example where containers of gas that were initially separated are now touching

one another, then the numbers

for each system can drift due to

random microscopic interactions between parts of the two systems as above, for

example where containers of gas that were initially separated are now touching

one another, then the numbers ![]() for each system will drift towards

values corresponding to a common final value

for each system will drift towards

values corresponding to a common final value ![]() of

of ![]() for both

systems, which is the value for which

for both

systems, which is the value for which ![]() for the combined system is

maximized, when the total energy of the combined system is

for the combined system is

maximized, when the total energy of the combined system is ![]() .

.

If the initial values ![]() and

and ![]() of

of ![]() are such that

are such that

![]() , then the final common value

, then the final common value ![]() of

of ![]() cannot be such that

cannot be such that

![]() , for by the result above, that would

mean that the final energies

, for by the result above, that would

mean that the final energies ![]() and

and ![]() of the two systems

satisfy

of the two systems

satisfy

![]() and

and

![]() , in contradiction with the

conservation of the total energy of the combined system, which we found above

follows from Newton's laws or de Maupertuis's principle, and which implies

that

, in contradiction with the

conservation of the total energy of the combined system, which we found above

follows from Newton's laws or de Maupertuis's principle, and which implies

that

![]() . And similarly,

. And similarly, ![]() cannot be

such that

cannot be

such that

![]() , for by the result above, that would imply

, for by the result above, that would imply

![]() and

and

![]() , which again contradicts the conservation of the

total energy of the combined system. Thus we must have

, which again contradicts the conservation of the

total energy of the combined system. Thus we must have

![]() , so if

, so if

![]() , then

, then

![]() .

.

If

![]() , and each of the two systems contains at least one type

of object for which

, and each of the two systems contains at least one type

of object for which ![]() has different values for at least two different

bins, then from the result above,

has different values for at least two different

bins, then from the result above,

![]() and

and

![]() , so

, so

![]() , and

, and

![]() and

and

![]() , so the drift of the

numbers

, so the drift of the

numbers ![]() to their final values results in a net transfer of energy

from the second system to the first. The values of

to their final values results in a net transfer of energy

from the second system to the first. The values of ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and

![]() are determined by the requirement that

are determined by the requirement that

![]() , so that

, so that

![]() .

.

These results show that ![]() has the basic observed properties of

temperature, except that

has the basic observed properties of

temperature, except that ![]() increases where temperature decreases, and

conversely. To determine the relation between

increases where temperature decreases, and

conversely. To determine the relation between ![]() and temperature, we'll

consider the example of an ideal gas, which is a collection of randomly moving

non-interacting molecules of mass

and temperature, we'll

consider the example of an ideal gas, which is a collection of randomly moving

non-interacting molecules of mass ![]() , enclosed in a container. In

accordance with our assumptions above, we'll assume that each molecule behaves

approximately as though its mass is concentrated at a single point.

, enclosed in a container. In

accordance with our assumptions above, we'll assume that each molecule behaves

approximately as though its mass is concentrated at a single point.

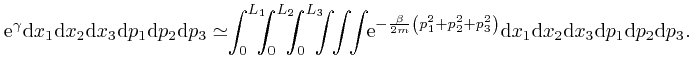

We'll take the container of the gas to be a box whose edges are aligned with

the Cartesian coordinate directions, such that the interior dimensions of the

box are ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . The total momentum of the molecules and the

box is 0 in accordance with our assumption above, so the position of the

centre of mass of the molecules and the box is independent of time. The

molecules are moving randomly in the interior of the box, and we'll assume

that the box is sufficiently rigid, and its mass is sufficiently large

compared to the mass

. The total momentum of the molecules and the

box is 0 in accordance with our assumption above, so the position of the

centre of mass of the molecules and the box is independent of time. The

molecules are moving randomly in the interior of the box, and we'll assume

that the box is sufficiently rigid, and its mass is sufficiently large

compared to the mass ![]() of each molecule, that we can treat the box to a good

approximation as staying in a fixed position. The ranges of the position

coordinates in the interior of the box are

of each molecule, that we can treat the box to a good

approximation as staying in a fixed position. The ranges of the position

coordinates in the interior of the box are

![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and

![]() . The potential energy

. The potential energy ![]() is 0 when all

the molecules are in the interior of the box, and

is 0 when all

the molecules are in the interior of the box, and ![]() when any of the

molecules is outside the interior of the box.

when any of the

molecules is outside the interior of the box.

We'll now divide the range of the possible positions and momenta of each

molecule into equal size bins as I described above, and we'll choose each bin

to be a box with its edges aligned with the Cartesian coordinate directions,

such that the length of each position edge of a bin is

![]() and the

difference between the values of a momentum coordinate at the ends of a

momentum edge of a bin is

and the

difference between the values of a momentum coordinate at the ends of a

momentum edge of a bin is

![]() . The sizes of the bin edges

. The sizes of the bin edges

![]() and

and

![]() are sufficiently small that we can treat

all the molecules in a bin as being approximately at the same position and

having approximately the same momentum, but sufficiently large that the number

of molecules in a bin is large. This is not a problem for gas containers of

everyday sizes, since the number of molecules in a cubic metre of air, to the

nearest power of 10, is about

are sufficiently small that we can treat

all the molecules in a bin as being approximately at the same position and

having approximately the same momentum, but sufficiently large that the number

of molecules in a bin is large. This is not a problem for gas containers of

everyday sizes, since the number of molecules in a cubic metre of air, to the

nearest power of 10, is about ![]() .

.

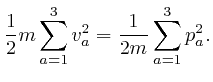

From above, the momentum ![]() of a molecule at position

of a molecule at position ![]() moving with speed

moving with speed

![]() is

is ![]() , so the kinetic energy of

the molecule is:

, so the kinetic energy of

the molecule is:

If ![]() is in the interior of the container, then the potential energy

is in the interior of the container, then the potential energy ![]() is

0, so from the formula above for the kinetic energy of a molecule:

is

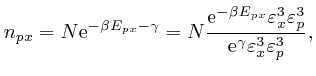

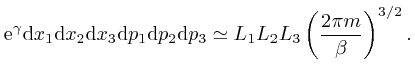

0, so from the formula above for the kinetic energy of a molecule:

If we did the calculations in the limit where the sizes

![]() and

and

![]() of the bin edges tend to 0, this formula would be exact. We

assumed above that

of the bin edges tend to 0, this formula would be exact. We

assumed above that

![]() and

and

![]() are sufficiently small

that we can treat all the molecules in a bin as being approximately at the

same position and having approximately the same momentum, so I'll treat this

formula as exact. We therefore have:

are sufficiently small

that we can treat all the molecules in a bin as being approximately at the

same position and having approximately the same momentum, so I'll treat this

formula as exact. We therefore have:

, so the value of

, so the value of

on the magnitudes

on the magnitudes

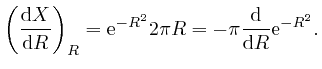

We'll complete the calculation of

![]() by first calculating

the number

by first calculating

the number

, and

we'll calculate this number by first calculating its square, which I'll

represent by

, and

we'll calculate this number by first calculating its square, which I'll

represent by

![]() . We can write this as:

. We can write this as:

is

is

or higher

powers of

or higher

powers of

Thus:

since

![]() . Thus

. Thus

![]() , since the limit of

, since the limit of

![]() as

as ![]() tends to

tends to ![]() is 0. Thus:

is 0. Thus:

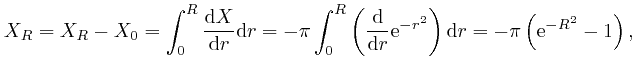

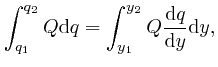

We now observe that according to the explanation I gave in the previous

post, here, of the meaning of the integral of a quantity, say ![]() , that

depends smoothly on another quantity, say

, that

depends smoothly on another quantity, say ![]() , over a range of values of

, over a range of values of ![]() ,

say from

,

say from ![]() to

to ![]() , where

, where

![]() , the range of

, the range of ![]() from

from ![]() to

to

![]() is divided up into a great number of tiny intervals, and the integral

is divided up into a great number of tiny intervals, and the integral

![]() is approximately the sum of a contribution

from each of these tiny intervals, such that the contribution from each tiny

interval is the value of

is approximately the sum of a contribution

from each of these tiny intervals, such that the contribution from each tiny

interval is the value of ![]() at some point in that tiny interval, times the

difference between the values of

at some point in that tiny interval, times the

difference between the values of ![]() at the ends of that tiny interval. The

exact value of the integral is the limit of sums of this form, as the tiny

intervals become so small and their number so great, that the size of the

largest tiny interval tends to 0. So if

at the ends of that tiny interval. The

exact value of the integral is the limit of sums of this form, as the tiny

intervals become so small and their number so great, that the size of the

largest tiny interval tends to 0. So if ![]() in turn depends on another

quantity, say

in turn depends on another

quantity, say ![]() , such that

, such that

![]() , the rate of

change of

, the rate of

change of ![]() with respect to

with respect to ![]() , is

, is ![]() for all values of

for all values of ![]() from

from ![]() to

to ![]() , then we have:

, then we have:

, and the error of this approximation tends to 0 more rapidly than

in proportion to

, and the error of this approximation tends to 0 more rapidly than

in proportion to

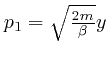

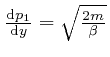

From this observation, with ![]() taken as

taken as

![]() ,

, ![]() taken as

taken as ![]() , and

, and ![]() taken as

taken as

,

so that

,

so that

,

,

, and

, and

, we find from

the result above that:

, we find from

the result above that:

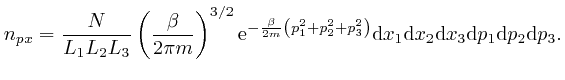

So from the formula above, the most likely number of molecules in a bin

centred at a position ![]() inside the container and momentum

inside the container and momentum ![]() , with edge

sizes

, with edge

sizes

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and

![]() , is:

, is:

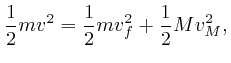

When an object of mass ![]() moving with velocity

moving with velocity

![]() collides with an object of mass

collides with an object of mass ![]() that is initially at

rest, and no other objects are involved, and the potential energy

that is initially at

rest, and no other objects are involved, and the potential energy ![]() is 0

except at the moment when the objects are in contact, then by the conservation

of total energy, which we obtained in the previous post, here, the

sum of the kinetic energies of the objects is the same before and after the

collision, and by the result we found above, the sum of the momenta of the

objects is the same before and after the collision. So if the final velocity

of the object of mass

is 0

except at the moment when the objects are in contact, then by the conservation

of total energy, which we obtained in the previous post, here, the

sum of the kinetic energies of the objects is the same before and after the

collision, and by the result we found above, the sum of the momenta of the

objects is the same before and after the collision. So if the final velocity

of the object of mass ![]() is

is ![]() , and the final velocity of the object of

mass

, and the final velocity of the object of

mass ![]() is

is ![]() , we have:

, we have:

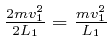

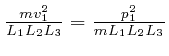

So if the 1 component of the velocity of a molecule of the ideal gas is ![]() at a particular time, then the only values the 1 component of the velocity of

that molecule ever takes are

at a particular time, then the only values the 1 component of the velocity of

that molecule ever takes are ![]() . If

. If ![]() , then that molecule

transfers momentum

, then that molecule

transfers momentum ![]() to the container wall at

to the container wall at ![]() , at moments

separated by time intervals

, at moments

separated by time intervals

![]() , so the average rate at which

that molecule transfers momentum to that container wall is

, so the average rate at which

that molecule transfers momentum to that container wall is

per unit time, so since force is the rate of change

of momentum, the average force exerted by that molecule on that container wall

is

per unit time, so since force is the rate of change

of momentum, the average force exerted by that molecule on that container wall

is

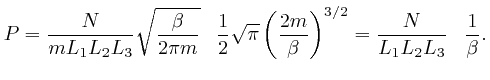

![]() in the outwards direction. Thus the pressure

in the outwards direction. Thus the pressure ![]() on

that container wall is the sum of

on

that container wall is the sum of

over all the

gas molecules in the container.

over all the

gas molecules in the container.

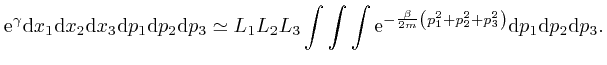

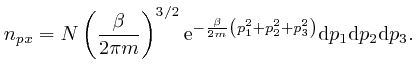

From the formula above, integrated over the volume of the container, the most

likely number of molecules in a momentum bin centred at momentum ![]() , with

edge sizes

, with

edge sizes

![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and

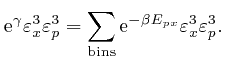

![]() , is:

, is:

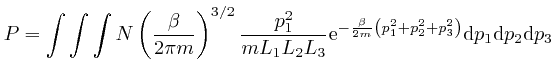

We'll assume now that this most likely number of molecules in each momentum

bin is the actual number of molecules in each momentum bin. Then the sum of

over all the gas

molecules in the container is:

over all the gas

molecules in the container is:

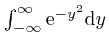

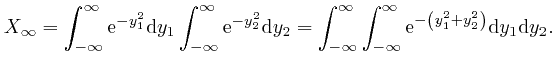

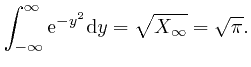

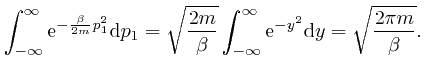

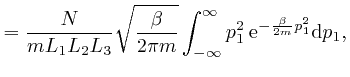

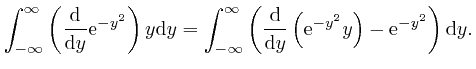

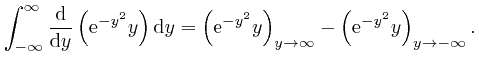

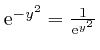

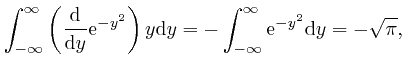

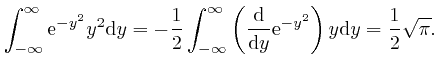

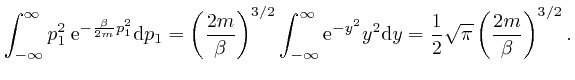

We'll calculate the above integral over ![]() by first calculating the

integral

by first calculating the

integral

. We

found above that

. We

found above that

, so:

, so:

, the magnitude of

, the magnitude of

tends rapidly to 0 as

tends rapidly to 0 as

, we have:

, we have:

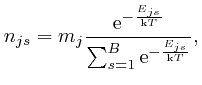

So if a system in thermal equilibrium at absolute temperature ![]() is composed

of a very large number microscopic objects of various types subject to

Newton's laws of motion, which we derived from de Maupertuis's principle of

stationary action in the previous post, here, and if the range of

possible positions and momenta of the objects is divided up into

is composed

of a very large number microscopic objects of various types subject to

Newton's laws of motion, which we derived from de Maupertuis's principle of

stationary action in the previous post, here, and if the range of

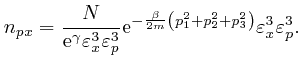

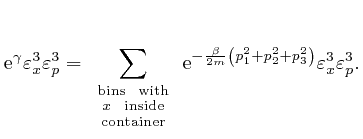

possible positions and momenta of the objects is divided up into ![]() tiny bins

of equal size, then from the result we found above, the most likely number of

objects of type

tiny bins

of equal size, then from the result we found above, the most likely number of

objects of type ![]() in position and momentum bin number

in position and momentum bin number ![]() is:

is:

One of the clues that led to the discovery of Dirac-Feynman-Berezin sums, and which made possible, among other things, the design and construction of the electronic device on which you are reading this blog post, came from the attempted application of the Boltzmann distribution to electromagnetic radiation. In the next post in this series, Electromagnetism, we'll look at the discoveries about electricity and magnetism that enabled James Clerk Maxwell, in the middle of the nineteenth century, to identify light as waves of oscillating electric and magnetic fields, and to calculate the speed of light from measurements of:

The software on this website is licensed for use under the Free Software Foundation General Public License.

Page last updated 4 May 2023. Copyright (c) Chris Austin 1997 - 2023. Privacy policy