| Home | Blog index | Previous | Next | About | Privacy policy |

By Chris Austin. 29 November 2020.

An earlier version of this post was published on another website on 17 November 2012.

This is the fourth in a series of posts about the foundation of our understanding of the way the physical world works, which I'm calling Dirac-Feynman-Berezin sums. The previous post in the series is Electromagnetism.

As in the previous posts, I'll show you some formulae and things like that along the way, but I'll try to explain what all the parts mean as we go along, if we've not met them already, so you don't need to know about that sort of thing in advance.

One of the clues that led to the discovery of Dirac-Feynman-Berezin sums came from the attempted application to electromagnetic radiation of discoveries about heat and temperature. We looked at those discoveries about heat and temperature in the second post in the series, and in the third post, we looked at how James Clerk Maxwell, just after the middle of the nineteenth century, was able to identify light as waves of oscillating electric and magnetic fields, and to calculate the speed of light from measurements of electrical and magnetic effects. Dirac-Feynman-Berezin sums for a physical system depend on a property of the system called its action, and in the first post in the series, we derived Sir Isaac Newton's second law of motion from Pierre-Louis de Maupertuis's principle of stationary action.

From our study of the way heat and temperature arise from the random motions of large numbers of microscopic objects, in the second post in the series, the existence of a well-defined temperature, in a region that is in thermal equilibrium, is a consequence of the conservation of energy, which we derived in the first post in the series, here, for a collection of objects subject to Newton's laws of motion, such that the potential energy of the objects depends only on their positions.

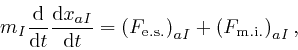

The energy of a physical system is related to the way the action of the

system

depends on the state of the system, and on what is happening in the system.

Today we'll find the action for

electromagnetic fields and electrically charged particles in

a vacuum, such that de Maupertuis's principle leads to Maxwell's equations

for the voltage field ![]() and the vector potential field

and the vector potential field

![]() , as in the previous post,

here

and

here,

and the electrostatic and magnetic forces on a

charged particle, as in the previous post,

here

and

here.

Then we'll find the conserved energy of the system from its action.

, as in the previous post,

here

and

here,

and the electrostatic and magnetic forces on a

charged particle, as in the previous post,

here

and

here.

Then we'll find the conserved energy of the system from its action.

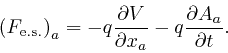

From the formula for the electric field strength ![]() in terms of the voltage

field

in terms of the voltage

field ![]() and the vector potential field

and the vector potential field ![]() , in the previous post,

here, the formula for the

electrostatic force

, in the previous post,

here, the formula for the

electrostatic force

![]() on a particle of electric charge

on a particle of electric charge ![]() ,

here, becomes:

,

here, becomes:

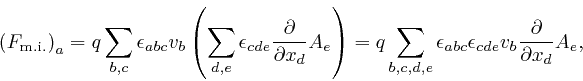

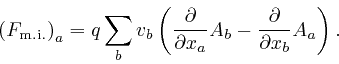

And from the formula for the magnetic induction field ![]() in terms of the vector potential field

in terms of the vector potential field ![]() , in the previous post,

here, the formula

for the magnetic induction force

, in the previous post,

here, the formula

for the magnetic induction force

![]() on a particle of electric

charge

on a particle of electric

charge ![]() moving with velocity

moving with velocity ![]() ,

here, becomes:

,

here, becomes:

where as in the previous post,

here, each index

![]() from the start of the

lower-case English alphabet can take values 1, 2, 3. From the formula in the

previous post,

here,

and a calculation similar to the one in the previous post,

here, this simplifies to:

from the start of the

lower-case English alphabet can take values 1, 2, 3. From the formula in the

previous post,

here,

and a calculation similar to the one in the previous post,

here, this simplifies to:

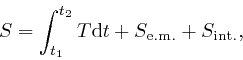

The action of a collection of electrically charged point particles moving

slowly compared to the speed of light in a vacuum, and the voltage field ![]() and the vector potential field

and the vector potential field ![]() , is:

, is:

where ![]() is the kinetic energy of the particles, as in the first

post in the series,

here. The

electromagnetic action

is the kinetic energy of the particles, as in the first

post in the series,

here. The

electromagnetic action

![]() is:

is:

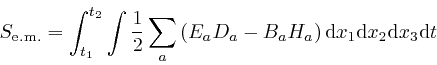

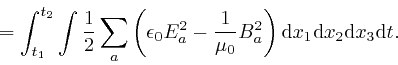

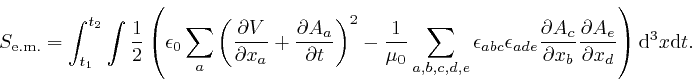

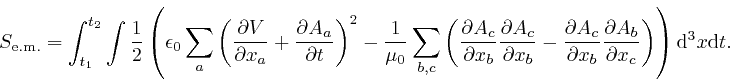

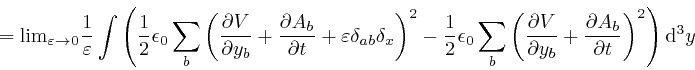

The integral

![]() is

over all space, and is often abbreviated to

is

over all space, and is often abbreviated to

![]() . From the formulae for the electric field strength

. From the formulae for the electric field strength ![]() and the magnetic

induction field

and the magnetic

induction field ![]() in terms of the voltage field

in terms of the voltage field ![]() and the vector potential

field

and the vector potential

field ![]() , as in the previous post,

here and

here, we find:

, as in the previous post,

here and

here, we find:

From the formula in the previous post, here, and a calculation similar to the one in the previous post, here, we find:

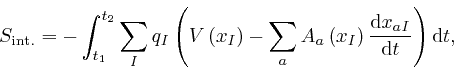

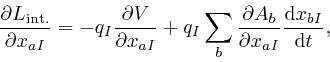

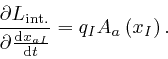

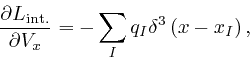

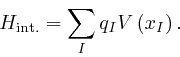

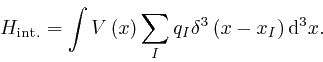

The interaction action

![]() is:

is:

where the notation is the same as we used in the first post in the series,

here,

and ![]() now represents the list of the electric charges of all the particles,

so that

now represents the list of the electric charges of all the particles,

so that ![]() is the electric charge of the

is the electric charge of the ![]() 'th particle.

'th particle.

It is convenient to let a single symbol, say ![]() , represent the entire

collection of data that includes the position data

, represent the entire

collection of data that includes the position data ![]() of all the particles at

all times, the value of the voltage field

of all the particles at

all times, the value of the voltage field ![]() at all positions and times, and

the values of the three components of the vector potential field

at all positions and times, and

the values of the three components of the vector potential field ![]() at all

positions and times. We'll let indexes

at all

positions and times. We'll let indexes

![]() distinguish the

quantities in the collection

distinguish the

quantities in the collection ![]() at each time

at each time ![]() . The possible values of

each index

. The possible values of

each index

![]() are

are ![]() , the

, the ![]() 'th position coordinate of

the

'th position coordinate of

the ![]() 'th particle;

'th particle; ![]() , the value of the voltage field at position

, the value of the voltage field at position ![]() ;

and

;

and ![]() , the value of the

, the value of the ![]() 'th component of the vector potential field

at position

'th component of the vector potential field

at position ![]() .

. ![]() or

or

![]() means the value of the

quantity

means the value of the

quantity ![]() at time

at time ![]() , so

, so

![]() ;

;

![]() ; and

; and

![]() . This sort of notation is called DeWitt's

compact index notation, after

Bryce DeWitt.

. This sort of notation is called DeWitt's

compact index notation, after

Bryce DeWitt.

A sum such as ![]() means a sum over all possible values of the index

means a sum over all possible values of the index ![]() ,

and where the possible values are continuous, as in the position index of

,

and where the possible values are continuous, as in the position index of

![]() and

and ![]() , it means an integral over the possible values. The

possible values of the index

, it means an integral over the possible values. The

possible values of the index ![]() correspond to the dynamical quantities that

can vary independently, which are called "degrees of freedom". Thus

correspond to the dynamical quantities that

can vary independently, which are called "degrees of freedom". Thus

![]() means a sum over the degrees of freedom.

means a sum over the degrees of freedom.

To extend the definition of

![]() , as in the first

post in the series,

here, to a

quantity

, as in the first

post in the series,

here, to a

quantity ![]() that depends on a collection of data such as

that depends on a collection of data such as ![]() , where the range

of possible values of an index such as

, where the range

of possible values of an index such as ![]() that distinguishes the quantities

in the collection includes continuous ranges of values, I'll first restate the

definition of

that distinguishes the quantities

in the collection includes continuous ranges of values, I'll first restate the

definition of

![]() in terms of the Kronecker

delta

in terms of the Kronecker

delta ![]() , which I defined in the first

post in the series,

here.

The range of possible values of

the indexes

, which I defined in the first

post in the series,

here.

The range of possible values of

the indexes ![]() and

and ![]() here can be any discrete range of values: the

definition of the Kronecker delta

here can be any discrete range of values: the

definition of the Kronecker delta ![]() that I used in the previous post,

here, where the

indexes

that I used in the previous post,

here, where the

indexes ![]() and

and ![]() can take values 1, 2, or 3, is a special case.

can take values 1, 2, or 3, is a special case.

In the context of the notation where ![]() represents a collection of

quantities, and the index

represents a collection of

quantities, and the index ![]() distinguishes the quantities in the collection,

the expression

distinguishes the quantities in the collection,

the expression ![]() represents the collection of quantities such that

represents the collection of quantities such that

![]() . Thus the expression

. Thus the expression

![]() represents the collection of quantities such that

represents the collection of quantities such that

![]() for

for ![]() , and

, and

![]() . Thus we can restate the definition of

. Thus we can restate the definition of

![]() , as in the first

post in the series,

here, as:

, as in the first

post in the series,

here, as:

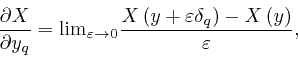

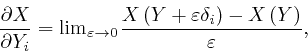

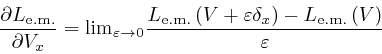

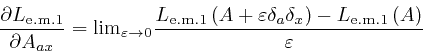

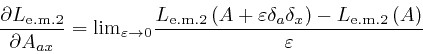

where

![]() means the limit of what

follows it, as

means the limit of what

follows it, as ![]() tends to 0. In words,

tends to 0. In words,

![]() is the rate of change of a quantity

is the rate of change of a quantity ![]() that depends on a

collection of quantities

that depends on a

collection of quantities ![]() , as the quantity

, as the quantity ![]() changes, while all the

other quantities in

changes, while all the

other quantities in ![]() have fixed values.

have fixed values.

A quantity ![]() that depends on a discrete collection of quantities

that depends on a discrete collection of quantities ![]() , some

of which can take continuous values, is sometimes said to be a function of

, some

of which can take continuous values, is sometimes said to be a function of

![]() . For example

. For example

![]() , which we studied

in the first post in the series,

here, is said to be a

function of the angle

, which we studied

in the first post in the series,

here, is said to be a

function of the angle ![]() . A quantity

. A quantity ![]() that depends on a collection

of quantities such as

that depends on a collection

of quantities such as ![]() , where the range of possible values of an index such

as

, where the range of possible values of an index such

as ![]() that distinguishes the quantities in the collection

that distinguishes the quantities in the collection ![]() includes

continuous ranges of values, is sometimes said to be a "functional" of

includes

continuous ranges of values, is sometimes said to be a "functional" of ![]() .

For example the action

.

For example the action ![]() ,

above,

is a functional of the position data

,

above,

is a functional of the position data ![]() of the particles, the voltage field

of the particles, the voltage field ![]() , and the vector potential field

, and the vector potential field ![]() .

.

To extend the definition of

![]() for a function

for a function

![]() of

of ![]() to

to

![]() for a functional

for a functional ![]() of

of ![]() ,

we'll use the analogue of the Kronecker delta

,

we'll use the analogue of the Kronecker delta ![]() for continuous

indexes, which is called the Dirac delta after

Paul Dirac. If

for continuous

indexes, which is called the Dirac delta after

Paul Dirac. If ![]() is a

quantity that can take continuous values, for example time or a position

coordinate, then the Dirac delta

is a

quantity that can take continuous values, for example time or a position

coordinate, then the Dirac delta

![]() is the limit as

is the limit as

![]() tends to 0 of a family of smooth functions

tends to 0 of a family of smooth functions

![]() of

of

![]() that have a high peak at

that have a high peak at ![]() , such that

, such that

![]() for all

for all ![]() , and

, and

![]() tends to 0 as

tends to 0 as ![]() tends to 0 for all

tends to 0 for all ![]() . For example

. For example

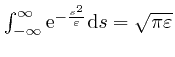

![]() could be

could be

, since by a calculation

similar to the one in the second post in the series,

here, we find that

, since by a calculation

similar to the one in the second post in the series,

here, we find that

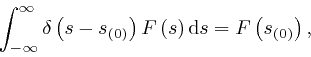

. The Dirac

delta has the property that for any function

. The Dirac

delta has the property that for any function ![]() of

of ![]() :

:

which is analogous to the property of the Kronecker delta we observed in the previous post, here.

We'll now extend the definition of the Kronecker delta and the Dirac delta to

the indexes

![]() that distinguish the quantities in the

collection

that distinguish the quantities in the

collection ![]() at each time

at each time ![]() in the appropriate way, using the Dirac delta

where the ranges of possible values of the indexes are continuous. Thus

we'll define

in the appropriate way, using the Dirac delta

where the ranges of possible values of the indexes are continuous. Thus

we'll define

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and

![]() . Here

. Here ![]() in the context

in the context ![]() or

or ![]() is understood from its context to represent a position in space,

like

is understood from its context to represent a position in space,

like ![]() in the same context. With these definitions,

in the same context. With these definitions, ![]() is 1 if

is 1 if

![]() and

and ![]() represent the same degree of freedom and 0 otherwise, and the

Kronecker delta is used in contexts where the sum

represent the same degree of freedom and 0 otherwise, and the

Kronecker delta is used in contexts where the sum ![]() means a discrete

sum, and the Dirac delta is used in contexts where it means an integral.

means a discrete

sum, and the Dirac delta is used in contexts where it means an integral.

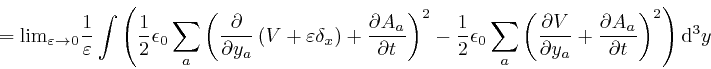

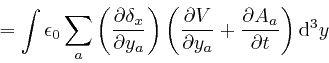

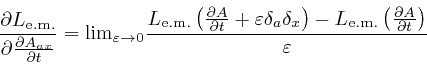

We can now define

![]() for a functional

for a functional ![]() of

of

![]() as:

as:

where in the context of the notation where ![]() represents a collection of

quantities, and the index

represents a collection of

quantities, and the index ![]() distinguishes the quantities in the collection,

the expression

distinguishes the quantities in the collection,

the expression ![]() represents the collection of quantities such that

represents the collection of quantities such that

![]() .

.

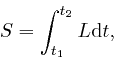

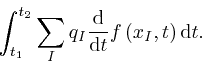

We now observe that the formula for the action ![]() ,

above, can be written as:

,

above, can be written as:

where

and

![]() and

and

![]() are the expressions that are integrated from

are the expressions that are integrated from ![]() to

to ![]() in the formulae

for

in the formulae

for

![]() ,

above, and

,

above, and

![]() above. The expression

above. The expression ![]() is called the Lagrangian, after

Joseph-Louis Lagrange,

who vigorously developed the applications of de Maupertuis's principle.

is called the Lagrangian, after

Joseph-Louis Lagrange,

who vigorously developed the applications of de Maupertuis's principle.

We observe, furthermore, that at each time ![]() , the expressions

, the expressions ![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and

![]() , and

consequently also

, and

consequently also ![]() , depend on the dynamical quantities

, depend on the dynamical quantities ![]() , as

above,

only through the values of

, as

above,

only through the values of ![]() and

and

![]() at that

time

at that

time ![]() , or in other words, only through

, or in other words, only through ![]() and

and

![]() . Here I am interpreting

. Here I am interpreting

![]() as

as

![]() , since the symbol

, since the symbol

![]() is an alternative notation for

Leibniz's

is an alternative notation for

Leibniz's ![]() , as I

explained in the first post in the series,

here.

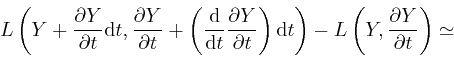

By calculations similar to those we did in the first post in the series,

here,

we find that when an action is the time integral of a

Lagrangian

, as I

explained in the first post in the series,

here.

By calculations similar to those we did in the first post in the series,

here,

we find that when an action is the time integral of a

Lagrangian ![]() , as above, such that

, as above, such that ![]() , the Lagrangian

, the Lagrangian ![]() at time

at time ![]() ,

depends on the dynamical quantities

,

depends on the dynamical quantities ![]() only through

only through ![]() and

and

![]() , the equations that result from

requiring that the action should be relatively unaltered by small changes in

the values of the dynamical quantities

, the equations that result from

requiring that the action should be relatively unaltered by small changes in

the values of the dynamical quantities ![]() and their time dependence, in

accordance with de Maupertuis's principle of stationary action, as above, are:

and their time dependence, in

accordance with de Maupertuis's principle of stationary action, as above, are:

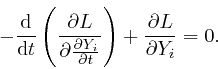

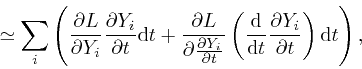

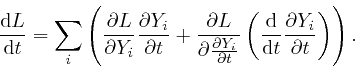

This is called Lagrange's equation. In this formula, the expressions

![]() and

and

![]() are defined by treating

are defined by treating ![]() and

and

![]() as completely independent

quantities. The change to the action that results from the replacement of

as completely independent

quantities. The change to the action that results from the replacement of

![]() by

by

![]() , where

, where

![]() is small for all

is small for all ![]() and

all

and

all ![]() , is the time integral of the sum

, is the time integral of the sum ![]() of

of ![]() times the

left-hand side of the above equation, plus terms that tend to 0 more rapidly

than in proportion to

times the

left-hand side of the above equation, plus terms that tend to 0 more rapidly

than in proportion to ![]() , as

, as ![]() tends to 0.

tends to 0.

We'll now use Lagrange's equation, as above, to find the equations that result

from the application of de Maupertuis's principle to the action ![]() ,

above. For

,

above. For

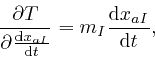

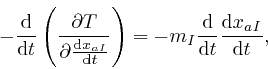

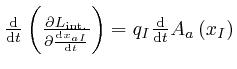

![]() , we find from the formula for the kinetic energy

, we find from the formula for the kinetic energy

![]() of the particles, as in the first post in the series,

here, that:

of the particles, as in the first post in the series,

here, that:

where I used Leibniz's rule for the rate of change of a product, which we obtained in the first post in the series, here. Thus:

which is in agreement with the result we found in the first post in the series,

here. ![]() does not depend on

does not depend on ![]() other than through

other than through

![]() , and from the formula for

, and from the formula for

![]() ,

above,

,

above,

![]() does not depend on

does not depend on ![]() or

or

![]() . From the formula for

. From the formula for

![]() ,

above, we find:

,

above, we find:

For the first of the above two formulae, I rewrote the dummy index ![]() that is

summed over by

that is

summed over by ![]() in the formula for

in the formula for

![]() as

as ![]() , to avoid confusing it

with the index

, to avoid confusing it

with the index ![]() on the quantity

on the quantity ![]() we are evaluating the rate of

change of

we are evaluating the rate of

change of

![]() with respect to.

with respect to.

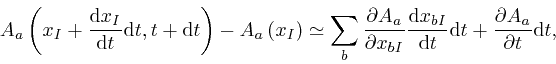

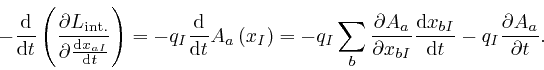

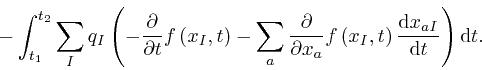

To calculate

, we observe that by the result we found in the first

post in the series,

here, with

, we observe that by the result we found in the first

post in the series,

here, with ![]() taken as

taken as

![]() , and the

, and the ![]() taken as

taken as ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , we

have:

, we

have:

where the error of this approximate representation tends to 0 more rapidly

than in proportion to ![]() , as

, as ![]() tends to 0. For a

formula such as this one, where we have not yet divided the change during time

tends to 0. For a

formula such as this one, where we have not yet divided the change during time

![]() by

by ![]() , we relax the rule that Leibniz's

, we relax the rule that Leibniz's

![]() means that the formula is to be taken in the limit where

means that the formula is to be taken in the limit where

![]() tends to 0, because the formula would otherwise give

tends to 0, because the formula would otherwise give ![]() . On dividing the above formula by

. On dividing the above formula by ![]() , and then taking the limit

where

, and then taking the limit

where ![]() tends to 0, we find:

tends to 0, we find:

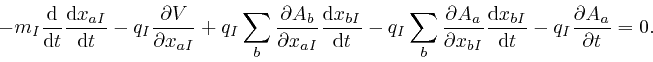

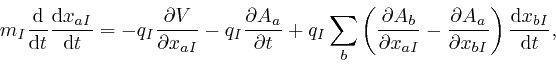

Thus from Lagrange's equation, above, we have:

Rearranging this formula as:

we recognize it as:

where

![]() is the electrostatic force, as

above, on the

is the electrostatic force, as

above, on the ![]() 'th particle, and

'th particle, and

![]() is the

magnetic induction force, as

above, on the

is the

magnetic induction force, as

above, on the ![]() 'th particle.

'th particle.

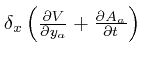

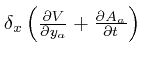

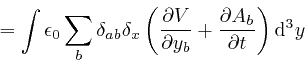

For ![]() ,

, ![]() gives no contribution. From the formula for

gives no contribution. From the formula for

![]() ,

above, we find:

,

above, we find:

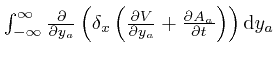

In the second line here, I rewrote the dummy position index ![]() that is

integrated over by

that is

integrated over by

![]() in the formula for

in the formula for

![]() as

as ![]() , to avoid confusing it with the index

, to avoid confusing it with the index ![]() on the

quantity

on the

quantity ![]() we are evaluating the rate of change of

we are evaluating the rate of change of

![]() with respect to.

with respect to. ![]() means

means

![]() ,

in accordance with the definitions

above and

above.

The fourth line is obtained from the third

line in a similar manner to the calculation in the first post in the series,

here: we use

Leibniz's rule for

the rate of change of a product to calculate the rate of change of the product

,

in accordance with the definitions

above and

above.

The fourth line is obtained from the third

line in a similar manner to the calculation in the first post in the series,

here: we use

Leibniz's rule for

the rate of change of a product to calculate the rate of change of the product

with respect to

with respect to ![]() , then use the result that the

integral

, then use the result that the

integral

is the difference between the value of

is the difference between the value of

as

as ![]() tends to

tends to ![]() and its value as

and its value as ![]() tends to

tends to ![]() , which is 0, since

, which is 0, since

![]() is 0

in both these limits. And the fifth line is obtained from the fourth line by

using the result

above for the Dirac delta, with

is 0

in both these limits. And the fifth line is obtained from the fourth line by

using the result

above for the Dirac delta, with ![]() taken as

taken as ![]() and

and

![]() taken as

taken as ![]() , for

, for ![]() .

.

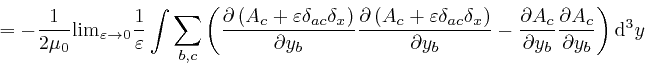

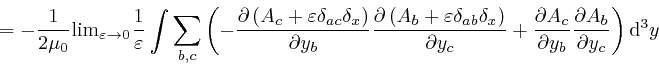

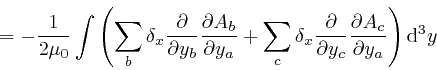

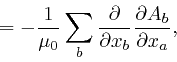

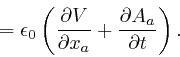

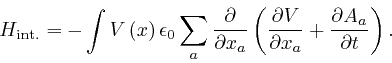

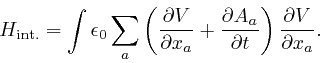

From the formula for

![]() ,

above, we also find:

,

above, we also find:

From the formula for

![]() ,

above,

we find:

,

above,

we find:

where

![]() , and:

, and:

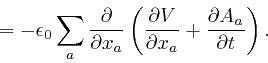

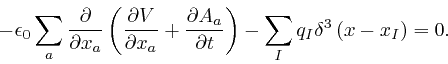

Thus from Lagrange's equation, above, we find:

This is in agreement with Maxwell's equation summarizing Coulomb's law, as

in the previous post,

here,

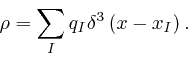

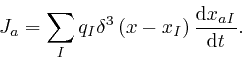

since for a collection of point particles at positions ![]() with

electric charges

with

electric charges ![]() , the electric charge density

, the electric charge density ![]() is:

is:

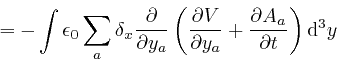

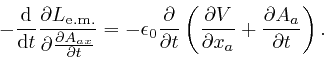

For

![]() ,

, ![]() again gives no contribution. From the

formula for

again gives no contribution. From the

formula for

![]() ,

above, two terms in

,

above, two terms in

![]() give

contributions to

give

contributions to

![]() , namely

the term involving

, namely

the term involving

![]() , which I shall call

, which I shall call

![]() , and the term

involving

, and the term

involving

![]() , which I shall call

, which I shall call

![]() . We find:

. We find:

where the successive steps are as in the corresponding calculation for ![]() , as

above,

and in the fourth line I also used the result we observed in the previous

post,

here,

for the Kronecker delta. And similarly:

, as

above,

and in the fourth line I also used the result we observed in the previous

post,

here,

for the Kronecker delta. And similarly:

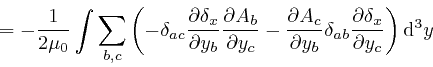

where the successive steps are the same again, and in going from the fourth

line to the fifth line, I rewrote the dummy index ![]() in the second term in

the fourth line as

in the second term in

the fourth line as ![]() .

.

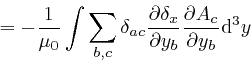

From the formula for

![]() ,

above, we also find:

,

above, we also find:

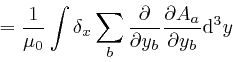

Thus:

From the formula for

![]() ,

above,

we find:

,

above,

we find:

Thus from Lagrange's equation, above, we find:

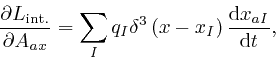

This is in agreement with Maxwell's equation summarizing Ampère's law, as

in the previous post,

here,

since for a collection of point particles at positions ![]() with

electric charges

with

electric charges ![]() , the electric current density

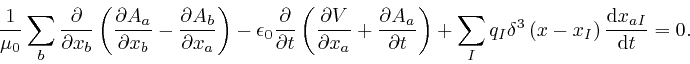

, the electric current density ![]() is:

is:

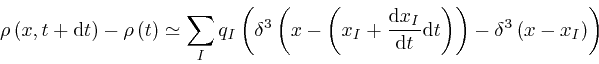

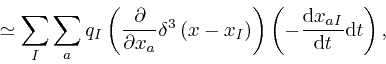

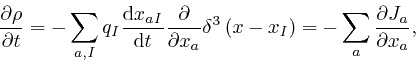

As a check of this formula for ![]() , we observe that for the electric charge

density

, we observe that for the electric charge

density ![]() of a collection of point particles at positions

of a collection of point particles at positions ![]() with

electric charges

with

electric charges ![]() , as

above,

the result we found in the first post in the series,

here, with

, as

above,

the result we found in the first post in the series,

here, with ![]() taken as

taken as

![]() and the

and the ![]() taken as

taken as ![]() , gives:

, gives:

where the error of this approximate representation tends to 0 more rapidly

than in proportion to ![]() , as

, as ![]() tends to 0. Thus:

tends to 0. Thus:

where the electric current density ![]() is as

above.

Thus the electric charge density

is as

above.

Thus the electric charge density ![]() of a collection of point particles at positions

of a collection of point particles at positions ![]() with electric charges

with electric charges ![]() , as

above,

and the electric current density

, as

above,

and the electric current density ![]() of those particles, as

above,

satisfy the equation expressing the conservation

of electric charge, as in the previous post,

here.

of those particles, as

above,

satisfy the equation expressing the conservation

of electric charge, as in the previous post,

here.

Thus for a collection of electrically charged point particles moving slowly

compared to the speed of light in a vacuum, the electrostatic force

![]() on those particles, as

above,

the magnetic induction force

on those particles, as

above,

the magnetic induction force

![]() on those particles, as

above,

Maxwell's equation

summarizing Coulomb's law, as in the previous post,

here,

and Maxwell's equation summarizing

Ampère's law, as in the previous post,

here,

all follow from the application of de Maupertuis's

principle of stationary action, as in the first post in the series,

here, to the action

on those particles, as

above,

Maxwell's equation

summarizing Coulomb's law, as in the previous post,

here,

and Maxwell's equation summarizing

Ampère's law, as in the previous post,

here,

all follow from the application of de Maupertuis's

principle of stationary action, as in the first post in the series,

here, to the action ![]() ,

above. And

Maxwell's equation summarizing

Faraday's

measurements involving time-dependent

magnetic fields, as in the previous post,

here,

and Maxwell's equation above summarizing the

non-observation of magnetic monopoles, as in the previous post,

here, are automatically satisfied,

due to the formulae expressing the electric field strength

,

above. And

Maxwell's equation summarizing

Faraday's

measurements involving time-dependent

magnetic fields, as in the previous post,

here,

and Maxwell's equation above summarizing the

non-observation of magnetic monopoles, as in the previous post,

here, are automatically satisfied,

due to the formulae expressing the electric field strength ![]() and the

magnetic induction field

and the

magnetic induction field ![]() in terms of the voltage field

in terms of the voltage field ![]() and the vector

potential field

and the vector

potential field ![]() , as in the previous post,

here.

, as in the previous post,

here.

We observe that the action ![]() ,

above,

is unaltered when the voltage field

,

above,

is unaltered when the voltage field ![]() and the vector potential field

and the vector potential field ![]() are changed by a gauge transformation, as

in the previous post,

here,

if the scalar field

are changed by a gauge transformation, as

in the previous post,

here,

if the scalar field ![]() that defines the gauge transformation is 0 at

the times

that defines the gauge transformation is 0 at

the times ![]() and

and ![]() between which the action is calculated. For the

first form of the formula for

between which the action is calculated. For the

first form of the formula for

![]() , as

above, shows that

, as

above, shows that

![]() only depends on

only depends on ![]() and

and ![]() through the electric field

strength

through the electric field

strength ![]() and the magnetic induction field

and the magnetic induction field ![]() , which are unchanged by the

gauge transformation, as we found in the previous post,

here. And the change to

, which are unchanged by the

gauge transformation, as we found in the previous post,

here. And the change to

![]() ,

above,

that results from the gauge transformation, is:

,

above,

that results from the gauge transformation, is:

The result we found in the first post in the series,

here, with ![]() taken as

taken as ![]() , and the

, and the ![]() taken as the

taken as the

![]() and

and ![]() , gives:

, gives:

where the error of this approximate representation tends to 0 more rapidly

than in proportion to ![]() , as

, as ![]() tends to 0. So:

tends to 0. So:

Thus the formula

above

for the change to

![]() , that results from the gauge

transformation, is:

, that results from the gauge

transformation, is:

So from the result we found in the first post in the series,

here,

that the integral of the rate of change of

a quantity is equal to the net change of that quantity, the change to

![]() , that results from the gauge

transformation, is 0 if

, that results from the gauge

transformation, is 0 if ![]() is 0 at

is 0 at ![]() and

and ![]() . Thus since

. Thus since ![]() , the

kinetic energy of the particles, does not depend on

, the

kinetic energy of the particles, does not depend on ![]() or

or ![]() , the action

, the action ![]() is unaltered by the gauge transformation, if

is unaltered by the gauge transformation, if ![]() is 0 at

is 0 at ![]() and

and ![]() . This property of

. This property of ![]() is called gauge invariance.

is called gauge invariance.

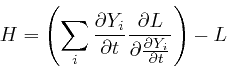

For any system whose action, ![]() , can be expressed in terms of a Lagrangian,

, can be expressed in terms of a Lagrangian,

![]() , as

above,

such that

, as

above,

such that ![]() , the Lagrangian at time

, the Lagrangian at time ![]() , depends on the

dynamical quantities

, depends on the

dynamical quantities ![]() only through

only through ![]() and

and

![]() , the values of

, the values of ![]() and

and

![]() at the time

at the time ![]() , so that de Maupertuis's principle of

stationary action leads to Lagrange's equation, as

above,

the following expression:

, so that de Maupertuis's principle of

stationary action leads to Lagrange's equation, as

above,

the following expression:

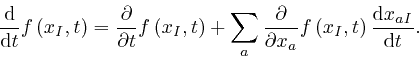

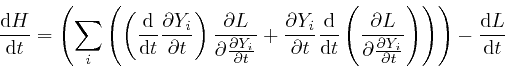

is automatically independent of time. For by Leibniz's rule for the rate of change of a product, which we obtained in the first post in the series, here:

where the second line follows from Lagrange's equation,

above.

And from the result we found in the first post in the series,

here, with ![]() taken as

taken as ![]() , and the quantities

, and the quantities ![]() taken

as the quantities

taken

as the quantities ![]() and

and

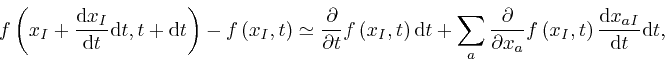

![]() , we have:

, we have:

where the error of this approximation tends to 0 more rapidly than in

proportion to ![]() , as

, as ![]() tends to 0. Thus:

tends to 0. Thus:

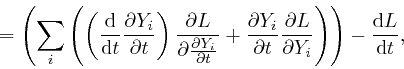

So from the formula above:

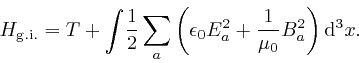

For a system that includes a collection of point particles, so that ![]() includes a term that is the kinetic energy

includes a term that is the kinetic energy ![]() of those particles, as

above,

the formula for

of those particles, as

above,

the formula for

![]() , as

above,

shows that

, as

above,

shows that

![]() , so that

, so that ![]() also includes a term

also includes a term ![]() . Thus

. Thus ![]() must be the total energy of the system, and the result that

must be the total energy of the system, and the result that

![]() , so that the value of

, so that the value of ![]() is

independent of time, expresses the conservation of energy.

is

independent of time, expresses the conservation of energy. ![]() is called the

Hamiltonian of the system, after

Sir William Rowan Hamilton.

is called the

Hamiltonian of the system, after

Sir William Rowan Hamilton.

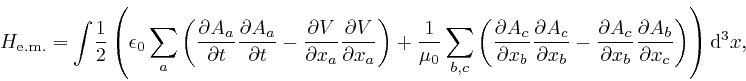

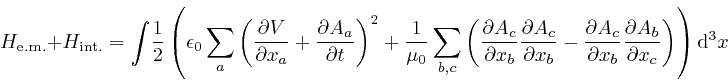

From the formulae for the action, ![]() , as

above,

, as

above,

![]() , as

above,

, as

above,

![]() , as

above,

, as

above,

![]() , as

above, and

, as

above, and

![]() , as

above,

we find that the Hamiltonian for a collection of electrically charged point

particles moving slowly compared to the speed of light in a vacuum, and the

voltage field

, as

above,

we find that the Hamiltonian for a collection of electrically charged point

particles moving slowly compared to the speed of light in a vacuum, and the

voltage field ![]() and the vector potential field

and the vector potential field ![]() , is:

, is:

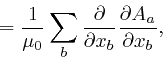

where ![]() is the kinetic energy of the particles, as

in the first post in the series,

here,

is the kinetic energy of the particles, as

in the first post in the series,

here,

and

The above formula for ![]() is not manifestly left unchanged by the gauge

transformations that modify the voltage field

is not manifestly left unchanged by the gauge

transformations that modify the voltage field ![]() and the vector potential

field

and the vector potential

field ![]() , as in the previous post,

here,

but leave the electric field strength

, as in the previous post,

here,

but leave the electric field strength ![]() and the

magnetic induction field

and the

magnetic induction field ![]() unaltered, and thus have no experimentally

observable consequences. However by the property of the Dirac delta we

observed

above,

we can write

unaltered, and thus have no experimentally

observable consequences. However by the property of the Dirac delta we

observed

above,

we can write

![]() ,

above, as:

,

above, as:

So when Maxwell's equation summarizing Coulomb's law, as above, is satisfied, we have:

When the number of electrically charged point particles is finite, ![]() and

and ![]() tend to 0 when any of the position coordinates

tend to 0 when any of the position coordinates ![]() tend to

tend to ![]() , so

by a calculation similar to the way we obtained the fourth line from the third

line in the calculation

above,

we find:

, so

by a calculation similar to the way we obtained the fourth line from the third

line in the calculation

above,

we find:

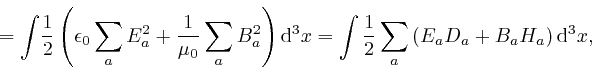

Thus:

where the second line here follows from reversing the steps that led from the

first version of the formula for

![]() , as

above,

to the final version, as

above.

, as

above,

to the final version, as

above.

Thus when the Lagrange equation that follows from the application of de

Maupertuis's principle to the action ![]() ,

above,

is satisfied, the Hamiltonian

,

above,

is satisfied, the Hamiltonian

![]() ,

above,

is equal to the gauge invariant Hamiltonian:

,

above,

is equal to the gauge invariant Hamiltonian:

Thus since

![]() when the Lagrange equation

is satisfied, we also have

when the Lagrange equation

is satisfied, we also have

when the Lagrange equation is satisfied.

when the Lagrange equation is satisfied.

![]() is the

manifestly gauge invariant formula for the total energy of a collection of

electrically charged point particles moving slowly compared to the speed of

light in a vacuum, and the electric field strength

is the

manifestly gauge invariant formula for the total energy of a collection of

electrically charged point particles moving slowly compared to the speed of

light in a vacuum, and the electric field strength ![]() and the magnetic

induction field

and the magnetic

induction field ![]() .

.

In the next post in this series,

Radiation in an oven,

we'll use the above formula for

![]() to look at how the discoveries about heat and temperature

that we looked at in the

second

post in the series, combined with the discoveries about electromagnetic

radiation that

we looked at in the

third

post, led to a seriously wrong conclusion about the properties

of electromagnetic radiation in a hot oven. In the post after that,

Dirac-Feynman sums,

we'll look at how the problem was resolved by the discoveries that led

to Dirac-Feynman-Berezin sums, which started with the identification

of a new fundamental constant of nature by

Max Planck, in 1899.

to look at how the discoveries about heat and temperature

that we looked at in the

second

post in the series, combined with the discoveries about electromagnetic

radiation that

we looked at in the

third

post, led to a seriously wrong conclusion about the properties

of electromagnetic radiation in a hot oven. In the post after that,

Dirac-Feynman sums,

we'll look at how the problem was resolved by the discoveries that led

to Dirac-Feynman-Berezin sums, which started with the identification

of a new fundamental constant of nature by

Max Planck, in 1899.

The software on this website is licensed for use under the Free Software Foundation General Public License.

Page last updated 4 May 2023. Copyright (c) Chris Austin 1997 - 2023. Privacy policy